Fascial Net Plastination Project

Fascial Net Plastination Project – January, 2018 by FRANCESCA PHILIP

There aren’t many reasons to visit Guben, Germany. With a population of only 1800, the town boasts little in the way of tourist attractions. In winter, the temperature rarely reaches positive digits, the streets are slick with ice, and the dark settles in hours earlier than it should. The grey sky is rather dull and gloomy. But that’s where I spent one week in January, my coat pulled up to the tips of my frozen Australian ears.

Guben was one of the most exciting experiences of my life.

On my first morning in town, I escaped the cold by stepping into a crowded entry foyer. The atmosphere was festive and bright. Old friends hugged and laughed, pink-cheeked, while new acquaintances echoed introductions. Every person had a different accent, a different title. I found some of my old friends, people I’d worked with on past projects—my buddy from Singapore, colleagues from San Francisco. Still, the air was thick with suspense.

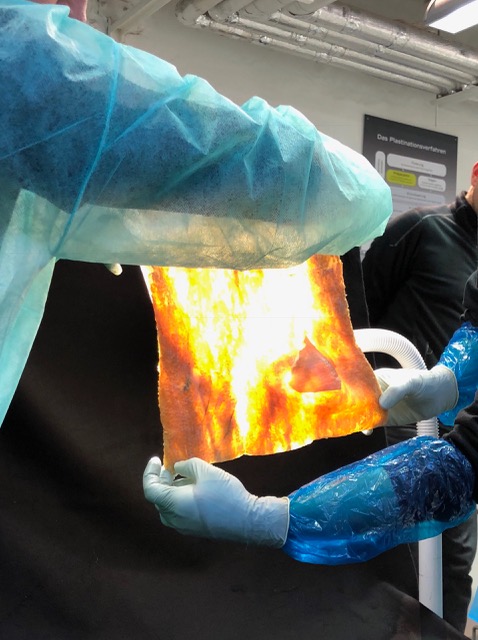

See, while Guben has few claims to fame, this building, the Gunther von Hagens’ Plastinarium, is one of them. All around us, thousands of plastinated models stood arranged—hearts, muscles, lungs, bones, all perfectly preserved in poses and museum cases. A few rooms over from the lobby was a laboratory, waiting for the gathered guests to don lab coats and level scalpels.

Photo credit: Jo Phee

Now is probably a good time to mention that all of us had flown into Guben for a human dissection workshop. Specifically, the Human Fascial Net Dissection and Plastination Project. We were anatomy nerds, and we were about to do more with fascia than anyone had ever done before.

Photo Credit: ©FasciaResearchSociety.org/plastination

This project was a long time in the making. It took years of appealing to the Plastinarium before Dr. Robert Schleip (Germany), a renowned fascial bodyworker and researcher, was finally authorized to lead our dissection team at the Guben laboratory. He and his co-leaders, John Sharkey (Ireland) and Dr. Carla Stecco (Italy), had a clear purpose: they wanted to study three-dimensional fascial anatomy on human bodies in an educational setting. In other words, they wanted our team to be the first in the world to plastinate fascia. If successful, the pieces produced would be presented at the Fascia Research Congress in Berlin in November 2018.

Coming at the workshop from a massage therapist’s point of view, I was excited that our project would give me an insight into the mechanisms of the body. For all my work in anatomy and movement education, I’ve always been frustrated at the limitations posed by textbook learning. Even working on bodies from the outside fails to give me a window into the real processes I’m trying to employ to heal and help my clients. Only interactive dissection courses have allowed me to appreciate crucial insight into how the body is really held together.

Of course, not every massage therapist loves the idea of working with cadavers. Some lack the financial resources for it; others lack the stomach. And both restrictions are understandable! But neither should be a barrier to a therapist’s education. That’s why plastination of fascia was a thrilling idea—finally, we would be able to take one of the least understood parts of the body out of the lab. With any luck, we would make fascia more than a buzzword. We would make it accessible.

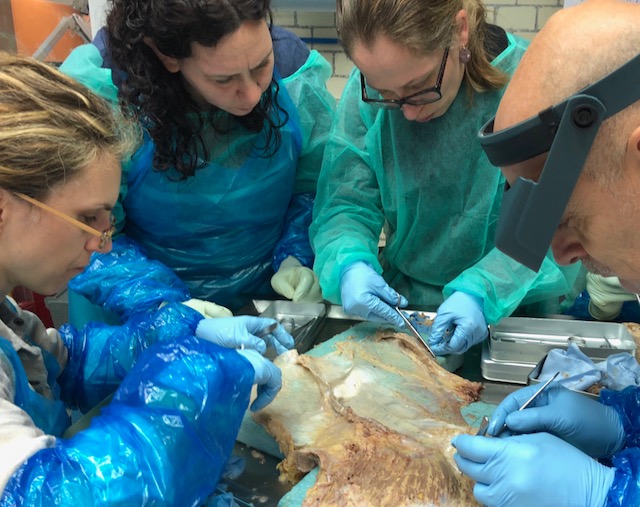

Our first day in the Plastinarium lab showed just what a diverse crew of participants we were. Our ranks included movement specialists, doctors, coroners, physical therapists, pilates and yoga teachers. John and Robert made it clear that such a combination was exactly what they’d hoped for. We were each to bring our passion and unique skillsets to the dissection table.

Photo Credit: ©FasciaResearchSociety.org/plastination

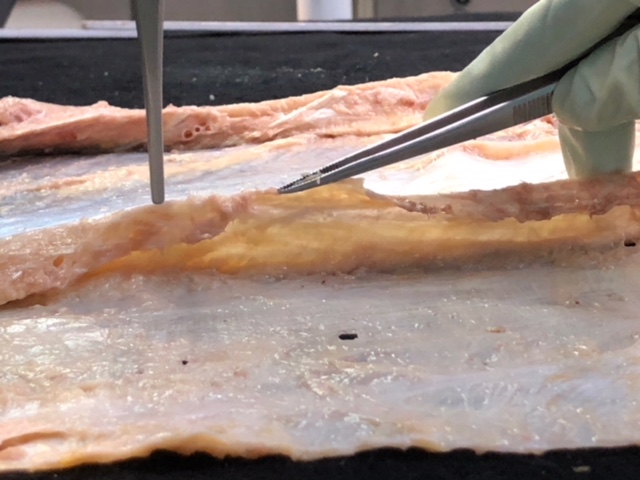

After a few introductory lectures, we began to brainstorm sub-projects. We broached and debated the benefits of dissecting full iliotibial bands, complete posterior diagonal lines, and superficial fascia of major joints. Often, the expert plastinarium staff would weigh in on which proposals might work and which would leave us with nothing but chemically-dissolved collagen. Together, we began to make progress.

Photo Credit: ©FasciaResearchSociety.org/plastination

By Thursday, the fourth day of the workshop, the steady thrum of work filled the lab. My group’s original attempt to render the fascia of the knee had failed. Rendering fascia, a process developed by Gil Hedley, requires you to dissolve the adipose globules from the structural network of fibers. After deciding we did not have sufficient time to produce a rendered piece, I moved from table to table, lending a hand where I was needed. There were so many projects that it was dizzying. While Robert had to leave mid-way through the day, Carla Stecco entered our midst with fresh passion and focus. With her to help guide us, no one’s hands were ever idle.

Photo Credit: ©FasciaResearchSociety.org/plastination

After hours of careful differentiation, I stepped back from work to take a breath. One of my colleagues did the same. We gazed at the room, awed by how enthralled everyone was in their tasks. “It looks like a dissection quilting bee,” she noted.

I blinked—it really did.

The next morning, my friend Jo Phee and I walked into the Plastinarium with the bittersweet awareness that this was our last day. Most of our projects lay completed, waiting only for the next stage of chemical treatment to make them permanent. Our final group discussion was analytical and reflective.

Photo Credit: ©FasciaResearchSociety.org/plastination

Deep questions arose: if fascia is the new frontier of anatomy, would this project contribute to a common good? Would the information gleaned be of any benefit or interest to humanity? The understanding of the importance of fascia is so ‘new’, with studies, research and applications coming from all corners of the globe. Would this small mission be a first step in doing together what we could not do alone?

I’d heard it said that if the body is considered the physical home of the heart and soul, then that would make fascia the locus of the emotions. Watching my colleagues grow from strangers to close friends after only one week of diving into fascial layers, I could only wonder if the spirit of the fascia somehow strengthened the connections we made. This group’s profound amount of collective wisdom truly inspired me.

That evening, I stood at the train station and waited for my train back to Berlin. Around me, Guben was much the same as it was on my arrival—dreary, grey and icy. My coat was still tucked up to the tips of my Australian ears. But there was a new fondness in my heart for the little town. It had given me opportunities I had never thought I would receive. In its streets, I’d walked with people I never thought I would ever work with. And in the Plastinarium lab, I had contributed to a project that I hoped would nudge the anatomical world just a little further.

On that platform, I called my husband, back at home in California. “Enjoy yourself,” he said. “You never know when you’ll be able to go back to Germany.”

“Oh, I do,” I said.

“You do?” he asked, surprised. “When?”

I grinned. “November, for the Fascia Research Congress.”

Francesca Philip

Francesca Philip has been in the high-tech industry, and is now a massage therapist, rehabilitation specialist, group fitness instructor, personal trainer, and Pilates instructor. Currently, she is considered a movement specialist. Her practical experience has allowed her to help seniors, students and athletes achieve their wellness and fitness goals. Fran is an Australian who now lives in Silicon Valley with her husband, daughter and lifetime collection of “great chats”.