Injured an arm? Train the other arm to gain strength

The concept of contralateral effects can be very important when rehabbing after an injury. If a limb in injured, whether it is a ligamentous sprain, broken bone, or a torn muscle, the immobilization necessary to allow time for it to heal, can result in muscle atrophy in that limb, resulting in decreased size and strength. Two weeks of inactivity of a limb can potentially led to as much as 33% loss in strength, a drop which is similar to aging many decades. And once the injury is healed, the person then faces a fairly long rehabilitation process to train and restore its strength.

It is known that stretching one side of the body can influence the flexibility of the contralateral, unstretched side of the body. This effect is also observed in strength training in which unilateral training of a limb enhances performance of the contralateral untrained limb. This phenomenon is often described as “cross education,” a term coined in 1894 by Scripture et al., and again in 1899 by Walter Davis. In another publication Researches on Cross Education, Davis quoted that it has been observed by G.F. Weber and communicated by Fechner in 1758.

This cross education effect has also been observed in several studies in which it has been termed “cross-training effects” or “contralateral effects.” For years, contralateral effects were debated. Researchers posited, they could be due to bad test practices, which confounded the results, or perhaps familiarity gained by the un-trained limb after having practiced it with the trained limb. However, more and more studies are confirming that contralateral effects are real.

New Study

A new study published in the April, 2018 issue of the Journal of Applied Physiology by researchers from the University of Saskatchewan studied contralateral effects in individuals who have atrophy of the musculature of a limb due to prolonged immobilization. This study tested the hypothesis that exercising muscles of a healthy, uninjured limb can prevent atrophy of the muscles of the contralateral immobilized limb.

The non-dominant forearm of 16 participants was immobilized with a cast. Participants were then randomly assigned to a resistance-training group in which the uncasted limb was trained (eccentric wrist flexion contraction, 3 times/week), or a control group that had no resistance training of the uncasted limb. The period of time of the study was one month.

Control Group: In the control group that had no resistance training, the wrist flexor musculature of the immobilized casted limb were, on average, more than 20 percent weaker; and those muscles had also shrunk in size, dropping approximately three percent of their mass.

Resistance-Training Group: In comparison, the resistance-training group showed strength preservation of the wrist flexor musculature of the immobilized limb that was not trained (as well as increased wrist flexor strength of the non-immobilized limb that was directly trained). Strength preservation was nonspecific to contraction type (in other words, strength preservation was found for all three types of muscle contractions: concentric, eccentric, and isometric). But strength preservation was specific to the wrist flexor musculature that was trained in the other limb.

These findings suggest that eccentric training of the non-immobilized limb can preserve size of the immobilized contralateral homologous musculature (or musculature that had the same functional joint action).

Mechanism?

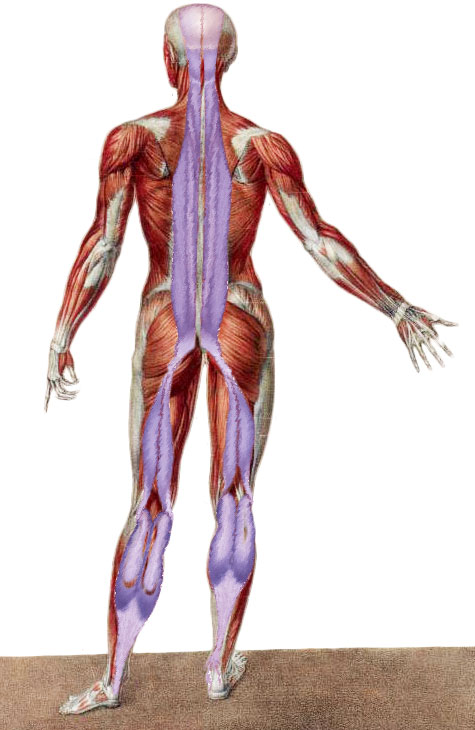

The authors believe that the mechanism for these contralateral effects is due to the changes in the nervous system during unilateral exercise that somehow reach and change the musculature on the other side of the body. Various biochemical substances might also be released by the working muscles and make their way to the corresponding contralateral muscles. But how the substances would manage to target the specific muscles in question is still unknown, so this explanation is less likely.

A review in 2017 suggested that to optimize contralateral strength improvements, cross-training sessions should involve fast eccentric sets with moderate volumes and rest intervals, e.g. 3-5 sets of 8-15 repetitions of eccentric contractions with rest times of 1-2 minutes between sets. And there is a direct relationship between the training load applied and the effect achieved.

Comment by Joseph Muscolino

The implications for contralateral effects are tremendous. Any patient/client who has had an injury, and therefore immobilization / disuse for a period of time, should be able to preserve the strength of the musculature of the immobilized limb by performing resistance training of the healthy, non-immobilized limb. This Canadian study specifically points to eccentric contraction, resistance training as the type of training that should be done. But further research might point to other choices. The importance though of contralateral effects is that the patient/client can avoid the loss of strength as well as the post-immobilization rehabilitation program that would then be necessary.