Lower Limb Biomechanics and Ilitiotobial Band Syndrome

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is a common overuse injury common with runners and cyclists. It is reported as the second most common cause of knee pain in runners and accounts for up to 12% of running injuries. The cause of ITBS could be a combination of several intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Many internet gurus seem to have their own say about what they think should be done. However, we need to actually read what scientific evidence says.

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is a common overuse injury common with runners and cyclists. It is reported as the second most common cause of knee pain in runners and accounts for up to 12% of running injuries. The cause of ITBS could be a combination of several intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Many internet gurus seem to have their own say about what they think should be done. However, we need to actually read what scientific evidence says.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by researchers from Sheffield, UK, published in the April-June 2019 issue of Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal evaluates lower-limb biomechanics and conservative interventions in ITBS.

The authors searched scientific databases and identified 18 studies. The authors found moderate evidence from prospective studies indicate possible mechanisms for ITBS:

1) greater hip adduction and knee internal rotation at footstrike and through stance, and

2) greater rearfoot eversion at foot strike.

These risk factors caused ITBS patients to reduce these activities to lower pain associated with ITB strain, ITB friction and compression. Thus, moderate evidence from case-control studies indicate ITBS participants exhibit:

1) reduced hip adduction,

2) greater knee and hip internal rotation at footstrike and through stance, and

3) reduced rearfoot eversion at foot strike.

Theory behind ITBS

The ITB is a connective tissue sheet lying level or just anterior to the lateral femoral epicondyle (LFE) at extension. Studies have reported antero-posterior translation and medio-laterally shift of the ITB fibres at the LFE during knee flexion.

A common hypothesis suggests ITBS is caused by the repetitive movement of the iliotibial band (ITB) sliding back and forth across the outer surface of the lateral epicondyle. This repeated friction caused an inflammation to the bursa between the LFE and ITB.

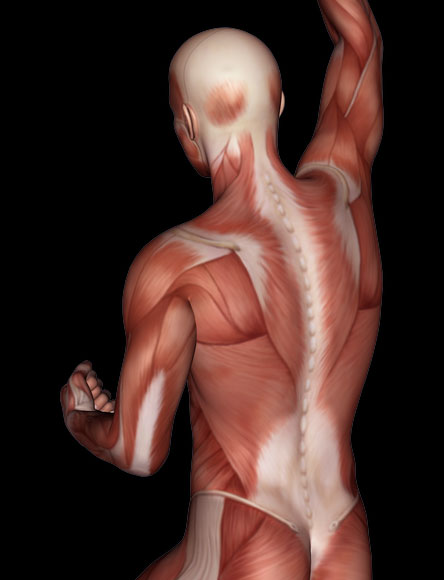

Another hypothesis suggests that ITB cannot create frictional forces by sliding back and forth over the epicondyle during flexion and extension of the knee. This hypothesis found no bursa between the LFE and ITB, and histological inspection reports a layer of highly vascularised and innervated adipose tissue with localised inflammation. This hypothesis suggests that ITBS is caused by increased compression of the highly vascularized and innervated layer of fat and loose connective tissue that separates the ITB from the epicondyle. The pain can be related to a chronic increased tension of the ITB caused by increased tension of the TFL or gluteus maximus muscles.

Nevertheless, several local, proximal, and distal mechanisms are involved in ITBS.

Local causes

Evidence from case-control studies found that subjects with ITBS exhibited a thicker ITB over the LFE compared with controls. This is likely to be an effect of chronic friction against the LFE. Repeated antero-posterior friction could affect connective tissue, the formation of a bursa, and an increase in ITB thickness resulting in ITBS.

Another study found an association between greater lateral epicondyle prominence and subjects with ITBS, suggesting an anatomic risk factor.

Proximal causes

Greater hip adduction is found to be a risk factor for ITBS, resulting in a loss of hip abductor strength in subjects with ITBS compared to the uninjured side and controls. A hypothesis suggests that increased hip adduction may move the attachment of the ITB medially, increasing ITB strain and its compression against the LFE and fat pad.

Greater knee internal rotation and greater femoral external rotation at footstrike and through stance represent a proximal risk factor for ITBS. A hypothesis suggests that greater femoral external rotation may be a result of weakness of the muscles at the hip (gluteus minimus, anterior fibers of gluteus medius, and tensor fascia latae), leading to an increase in LFE friction and fat pad compression by the ITB.

Distal causes

Greater rearfoot eversion at foot strike is a distal risk factor. ITBS subjects who demonstrated the highest rearfoot eversion also demonstrated high tibial internal rotation. A hypothesis suggests that an increase in these variables could result in increased ITB strain and fat pad compression.

Treatment

The authors found moderate evidence indicates that a six-week rehabilitation programme involving NSAID prescription, ITB stretching, and hip abductor strengthening reduces knee pain during physical activity, and prevents ITBS recurrence in the medium term (≤ 6 months).

Read also

- Iliotibial Band Syndrome: ITB cannot be stretched

- ITB: Empirical evidence is the reality—Robert Baker

- ITB: Extrapolating results from research to hands-on manual therapy should be done with caution—Joe Muscolino

- ITB: Our methods still get results; it’s our explanations that need updating —Til Luchau

- Can you stretch the ITB?