The Movement Kaleidoscope

The Power and the Grace by Joanne Elsphinston demystifies functional movement and integrates the science of movement with the art of teaching it. It aims to help the holistically minded movement professional achieve rewarding results in neuromuscular function.

This article is an extract from The Power and the Grace (copyright Handspring publishing, used with permission)

Imagine for a moment that your movement fits you like your favourite sweater. It is completely comfortable and completely expresses “you.” You feel that you can do anything in it: dress it up or dress it down, climb a mountain, or turn a cartwheel in it. You push your arms out into its sleeves and you are ready to go.

For movement to feel like this, many factors must play with one another. There is no single element that can transform a person’s movement into this very personal, harmonious, and effective expression of their intentions, drives, and desires. The body and brain together need a balanced diet of “movement nutrition” in order to flourish, and to explore the many physical and functional possibilities that we have as humans.

This integration of mind and body systems functions much like a kaleidoscope. Kaleidoscopes, humble sealed tubes containing a cascade of tiny glass pieces, create integrated and complex designs from the multi-coloured collection within it. A tiny twist of the kaleidoscope’s barrel changes the conditions, and a whole new design emerges that is as harmonious and coherent as the previous one. With another twist, the elements are reorganized again – the same elements are present, yet they offer a multitude of solutions. So it is with movement, where multiple processes within us work together to produce endless possibilities, ranging from extravagant forcefulness to dynamic stillness.

Instead of pieces of glass in a tube, we blend aspects of our thinking and emotional brains, our sensory and wider nervous system, and our musculoskeletal system to create patterns of movement to meet our daily needs and aspirations. We have a vast array of options available to us, but most of us display a mere fraction of our possible movement strategies. We are only turning our kaleidoscope through a few settings. As we shall see in later chapters, this is partly because our efficiency driven brains streamline their activity by creating movement templates based on prediction and expectation. These become the habitual strategies that we reproduce in our daily lives, which saves on energy but narrows the variety and adaptability of our movement. This not only decreases our options, but tends to load our bodies in repetitive ways, and can contribute to eventual injury.

We don’t realize that we are using ourselves in repetitive patterns. In fact, most of us are unaware of how we move at all, unless stopped by pain or injury. We tend to assume that the way in which we move is a preprogrammed inevitability, but the strategies that we develop don’t just arise from our own physical warehouse of possibilities: they can be influenced by our environment, our jobs, our emotional state, and even the habits and posture of the people around us. Our histories are written in our movement and posture, but we can choose what our future holds when we become aware of the flexibility of the nervous system and our body’s capacity for change.

To achieve this, we need a change in attitude. When our movement strategies aren’t meeting our needs, we tend to think of them as errors to be corrected. This assumes only two options: right or wrong. This is not only incredibly limiting but highly inaccurate. You have many possibilities available, but you are expressing an edited version that has been pruned and shaped over time. If your movement habits aren’t what you would like them to be, the answer lies in unearthing and reconnecting with some of the other possibilities that have been dormant. People who move well have more settings on their kaleidoscope: they are able to access more combinations of factors, giving them many options and allowing them to respond and adapt to a wider range of movement challenges. Fundamentally, people who don’t move well have fewer options – they are often locked into their habits, which reduces their adaptability and loads their body’s structures more repetitively. If our bodies are able to move in different ways, they can choose the best one for the job.

For health throughout our life span, therefore, our focus for exercise, training, and movement is to develop a wider range of effective, sustainable, and adaptable movement strategies. We want to maintain the integrity of our body over a wide variety of activities and contexts, to be able to create and control forces efficiently, to readily adapt to the new or unexpected, and to do so with confidence and spontaneity. In other words, we want not only to access more settings on our kaleidoscope but to see more colors inside it. This is clearly going to demand more than mere muscle activation – it will involve the seamless integration of multiple factors.

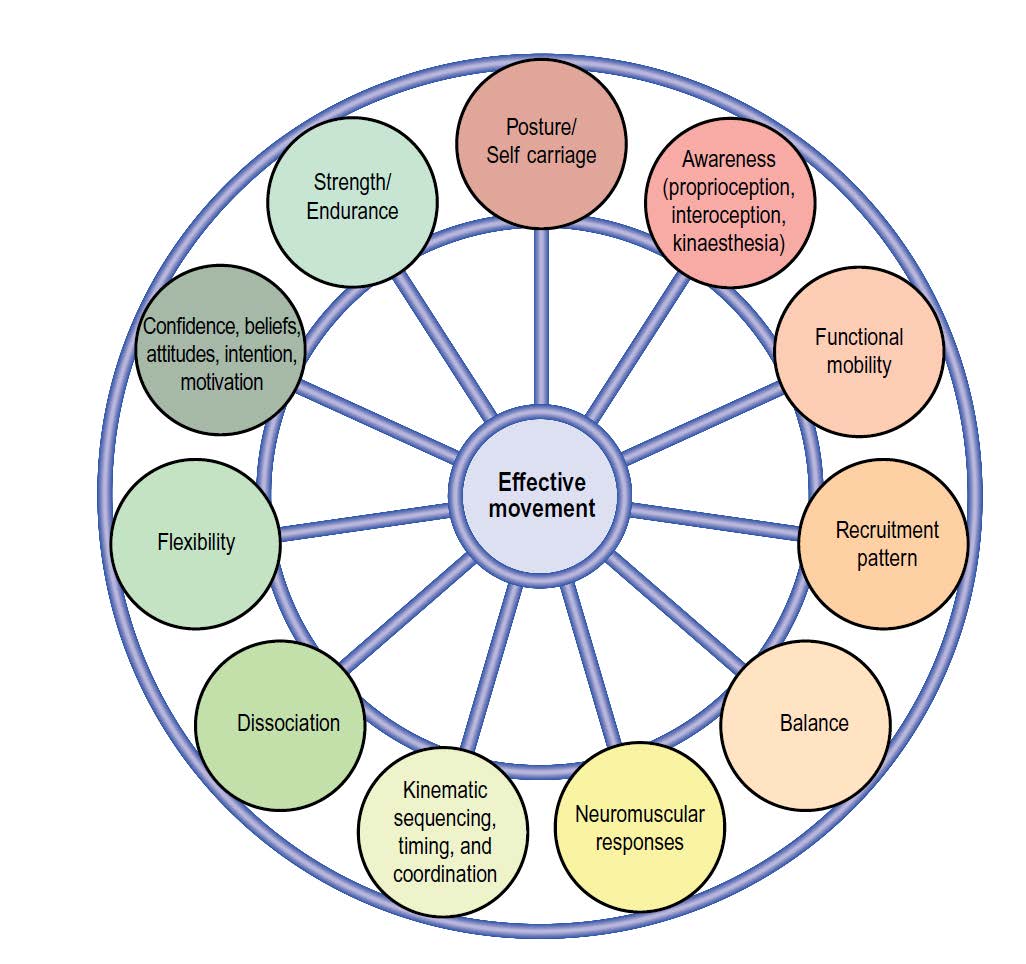

The wheel of interdependence

The wheel of interdependence is a simplified diagram, but it serves to illustrate just some of the many factors that influence and modify one another in the production of effective movement. At this point, some of the terms shown will be more familiar than others, but over the next few chapters in The Power and the Grace, you will become comfortable with each one.

If you are willing to challenge yourself, look at this collection of factors and note whether you feel more attracted to some than others, or secretly believe that some hold greater significance. If you find that this is the case, it is a wonderful start, because if we can identify our biases, we can set about overcoming them. More rewarding results and a deeper understanding for both you and your clients become possible.

To appreciate the interplay of factors on the wheel, let’s select functional mobility as an example. Functional mobility is the ability to move freely and with control through the full range of motion required as you perform a dynamic activity. Functional mobility is only possible if you already have flexibility, as this is what gives us the potential for a range of motion. Having a potential range of motion, however, doesn’t mean that we can actually use it during movement, nor that we can control any flexibility gains that we achieve.

In order to meaningfully integrate the flexibility potential, we must have dissociation, which is the ability to move our body segments independently of one another. Keeping the pelvis in place as the rib cage turns into rotation is an example of this.

Dissociation requires an appropriate pattern and level of muscle recruitment. If there is too much overall muscle recruitment, you cannot easily move one body segment away from another; instead they become fixed together, which makes you feel restricted.

Excessive muscle recruitment may be due to a number of physical or psychological factors. Selecting a task that is too advanced or heavy, trying too hard, or lacking confidence can all provoke this response. Let’s say, for example, that muscle tension is a reaction to a balance challenge. You start to wobble, and your senses tell you that there is too much movement, so you respond reflexively by contracting many muscles at once in an attempt to control the situation. This relatively immobilizes you, gluing your body parts together. If you attempt to move a limb with this process in play, you are thrown further off balance, as your muscles are working to resist the motion as you are trying to create it. You are pulling against yourself. You respond to this uncontrolled feeling by further increasing muscle tension, limiting your mobility even more. Your confidence becomes affected, your beliefs about your balance capability are reinforced, and above all you think to yourself that you really must do more stretching, because you don’t seem to be very flexible!

We bounce from one part of the wheel to another as factors connect, either working for us or against us. It is easy for us to fixate on one factor, without realizing that it is a relationship between factors that we need to develop instead. Our preferences come into play very readily, exposing our own biases. Most people, for example, will select flexibility rather than balance to work on, because improvements in it are so much more easily perceived, and this in turn feeds our motivation – although it doesn’t necessarily improve our overall performance.

What about strength? Surely this is an entity unto itself and not subject to the influences of other factors? Certainly, if you looked at a muscle’s performance in isolation, this might be the case. You can look at repetitions and sets, and how these create the necessary physiological stress to change how that muscle performs. This is potential building, but the ability to actually utilize that strength during a dynamic movement may be dependent upon other factors, for example, the timing and coordination of your body parts. This in turn may be influenced by functional mobility, which, as we have already seen, can be influenced by a number of other factors. It may also depend upon your balance, your awareness of body position, your confidence, and your intention. Even endurance is subject to the wheel – you may have physiological capacity, but if you over recruit muscles or have poor timing and coordination, it will cost you more energy over time as you move. There is no escaping the wheel

The control conundrum

The control concept has exploded in popularity over recent decades, and has developed a language and discourse that has gained widespread acceptance in the health and fitness industries. Unfortunately, it carries with it assumptions that do not necessarily match the research into its effectiveness, nor do they necessarily support the performance of normal movement. This has led to increasing controversy and conflict between professions.

Let’s take a look at a little core mythology. It is believed in some sectors that “all movement starts at the core.” This idea was boosted by neuromuscular research that identified that just prior to the body moving, the deep trunk musculature activates in preparation. Practitioners believed that this research endorsed the practice of consciously setting the abdominal wall in a fixed position prior to motion, and (in some sectors) into firm tensing of the abdominal wall to immobilize the lower spine. In many cases, however, this contradicts the biomechanics of normal movement.

If we look at the tennis forehand for example, force is generated in the legs, transferring via pelvic rotation through the torso to the upper body, which initiates its rotation just slightly later to allow elastic energy potential to develop across the myofascial structures on the front of the body. This is the “stretch and ping” that creates efficiency through effective force transmission, and it is dependent upon the independent motion, or dissociation, of upper and lower body segments. Having transferred from the ground upward, forces are finally funneled out to the racquet through the arm. The movement has started from the floor, not the core. The role of the “core” here is to connect and transfer forces between the upper and lower body, which requires an ability to move these segments relative to each other. The abdominals are not acting at a fixed length – instead they maintain connection while lengthening and shortening. This has very little relationship to the “preset and hold” approach taken in most gym classes.

Nevertheless, this practice continues, especially in the arena of low back pain rehabilitation.

The theory was simple: in the presence of pain, key muscles that contributed to control of joint segments were found to change their behavior.

It was assumed that an ensuing lack of control contributed to ongoing dysfunction, and therefore the area needed to be “stabilized” with specific training. The discourse was one of damage limitation and protection, carrying with it a subtext of threat of recurrence. This was easy to communicate and seemed very logical, especially to the frightened person in pain.

If we fast forward to the present time, it now appears that our conceptualization was naive. Analysis of years of research indicates that reducing people’s fear and catastrophic thoughts (catastrophizing) about their back pain has been shown to have more consistent influence on low back pain outcomes than transversus abdominis muscle activation. Taking active responsibility for one’s own personal health, learning to understand and interpret a range of new sensations in the body, overcoming unhelpful beliefs, and being challenged while supported with reassurance can all contribute to reducing helplessness, increasing confidence, and equipping a person with independent self-management tools. It is possible, then, that stability training may have a positive effect early on, but not necessarily for the reasons that its practitioners believe.

More is not necessarily better

Research on lower back, neck, knee, and hip injury indicates that too much muscular activity is associated with ongoing dysfunction. In other words, over controlling is emerging as a problem

Individuals with acute back pain actually demonstrate an increase in spinal stability, using more, rather than less muscle activity. This is a very natural initial response to protect an injured area, as you will know if you have ever experienced back pain. It is not helpful as an ongoing strategy, however. Constantly maintaining a protective activation pattern around the spine can compromise normal neuromuscular responses including the ability to make the small, sudden adjustments necessary in order to regain balance. Such adjustments require rapid but coordinated relaxation of the spinal muscles. The longer the delay in someone’s ability to relax these spinal muscles, the greater the risk of low back injury. Similar findings have been shown for knee and hip patients – too much muscle activity around the joints changes the way we use ourselves, compromising normal movement.

It is alarmingly easy to amplify this response in an injured person. People seek safety and reassurance when injured, and an explanation that promises protection of the injured part seems like a good idea. Co-contraction, the simultaneous activation of opposing muscles around a joint, has been promoted as the antidote to the threat of “uncontrolled movement.” Although it does initially provide a degree of functionality, co-contraction also creates an ongoing barrier to recovery; in fact, it may lead to recurrence later due to altered trunk dynamics. The “functional frozen” vigilantly control their previously injured area with various learned muscular setting behaviors. They come to believe that these behaviors protect them, but they actually end up preventing their bodies from regaining natural spontaneous movement responses. People trapped in this cycle have lost the overall goal of recovery, and instead make control their holy grail.

Can’t we just get stronger?

Strength is vitally important in maintaining musculoskeletal health across our lifespan. However, more strength cannot compensate for deficits in other systems, any more than increasing the size of a single jigsaw puzzle piece will create a complete picture by simply covering an empty space.

It is a fundamental error to assume that if you have enough strength to meet high load demands, you will cope with lower load situations competently. This is not the case: each should be viewed as having differing requirements. Strengthening involves high load tasks that demand commensurately high levels of muscle contraction, and this provides plenty of sensory feedback to let you know where your body parts are relative to one another. This doesn’t necessarily carry over to low load tasks, where you need a more finely tuned ability to process sensory feedback. For full spectrum function your brain needs to be able to hear the body’s whispers as well as its shouts. It is not unusual for people who struggle with body awareness to be attracted to high load training, as the strong feedback feels reassuring and pleasurable. To optimize their overall physical capability in the wider context of life, however, they need to improve their ability to sense themselves.

To develop strength in order to manage high loads, the complexity of the exercise is usually reduced in order to optimize force output. Common techniques requiring a very stable, bilateral foot position, such as squat and deadlift exercises, do not necessarily equip a person for a lower load task requiring speed, balance, proprioception, timing, and coordination for each leg separately.

For example, gluteal strength is not the sole deter mining influence on pelvic and knee control, but gluteal strengthening is nevertheless the most common approach for addressing it. This demonstrates the gap between what we are aiming for, and what we actually achieve. Studies on gluteal strength have demonstrated, first, that strength and knee control are not necessarily consistently correlated, and, second, that training of gluteal strength may not transfer to improved functional knee control. Gluteal muscle timing has been found to be an important factor in knee control for runners, and studies that have emphasized awareness of knee position during dynamic functional movements have yielded positive results, as did a neuromuscular program of mixed movement activities. This opens up many exciting possibilities for improving movement in simple ways, as we shall see in later chapters of The Power and the Grace.

This article is an extract from The Power and the Grace (copyright Handspring publishing, used with permission)