Pleasant Deep Touch, with Comments by Robert Schleip, PhD

New research shows that deep pressure elicits similar pleasantness and calming effect as the affective C-tactile touch. Touch perception and cortical activation patterns for these two different types of touch are similar but distinct. The peripheral sensory afferents that transduce these sensations are different. The Social-Affective Touch Hypothesis proposes that gentle stroking and deep pressure are two primary sensory inputs for pleasant, rewarding social touch.

Recent research has found that affective touch can induce positive mood, reduce anxiety or stress. It was theorised that affective massage therapy, which applies slow, rhythmic, and caress-like touch, stimulates C-tactile sensory afferents. These C tactile afferents C-tactile afferents are present only in hairy skin, and was hypothesisted to constitute a specialized pathway signalling “close, affiliative body contact with others.”

In massage therapy, deep pressure can also stimulate pleasurable experience, reduce depression, stress, and pain. These effects, however, involve interpersonal touch. Some would argue that deep pressure could also be affective. However, what happened when the human touch component is removed from deep pressure? Would it still be regarded as a pleasant touch?

A study was designed to see the effects of deep pressure (without human interpersonal touch) by applying a mechanical massage-like compression device and determine whether it would be perceived as pleasant using subjective test and a brain scan with MRI. The study was published in the journal Neuroscience. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306452220305030

The first experiment with 15 participants confirmed that deep pressure (applied using mechanical compression) is perceived as pleasant and calming. The second experiment involving 39 females comparing brushing and pressure, found that both stimuli were rated as pleasant. However, the stimuli differed in their ratings of pleasantness. The third experiment with 24 participants showed that the effect of deep pressure could be imaged using functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Deep pressure activates brain regions highly similar to those that respond to C-tactile affective stroking, as well as regions not activated by gentle stroking.

These investigations demonstrate that specific deep pressure is still considered pleasant even when applied mechanically. Oscillating deep pressure has similar affective effects to that of gentle stroking, including similar ratings of touch pleasantness and increased ratings of calm.

The authors propose that deep pressure activates a novel pleasant touch pathway. The authors hypothesised that pleasant and calming effects of deep affective pressure might play essential roles in social bonding. This is experienced in infants, who are often held tightly to the body, and the rhythmic breathing of the parent would create an oscillating pressure stimulus. Similarly, humans or animals huddling for warmth or sleeping in close contact would experience deep pressure. The relaxing effects of deep pressure may relate to the security and safety conferred by being held by others.

The authors propose that the C-tactile social/affective touch hypothesis needs to be extended to encompass the deep pressure sensory pathway as critical components of social touch.

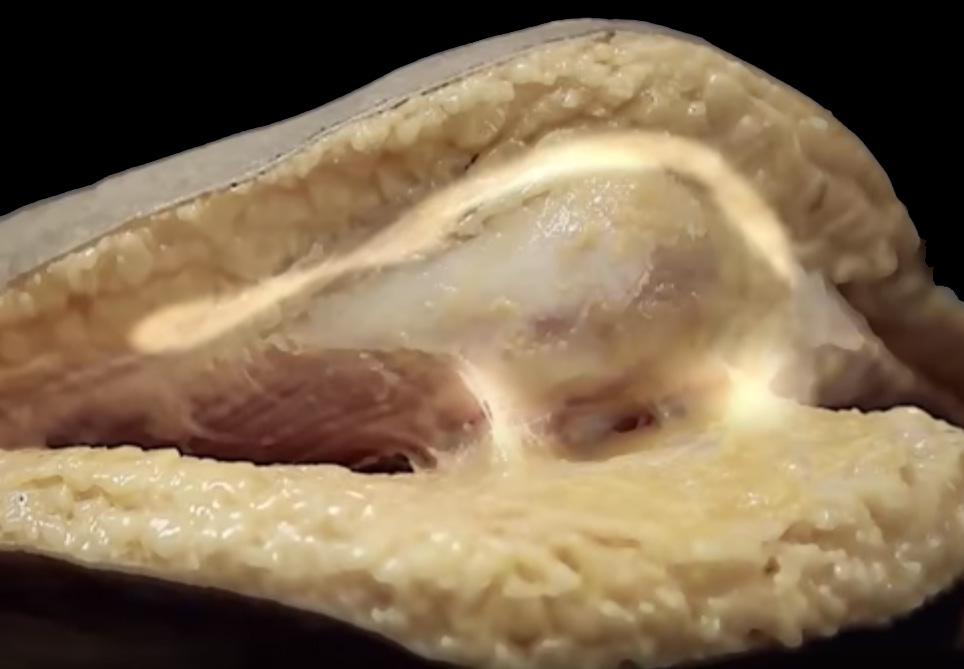

However, the authors indicated that C-tactile afferents do not convey pleasant deep pressure. Studies have found that sensations of deep pressure remain strong after anesthetization of the skin. This is likely due to the presence of pressure-sensitive afferents in muscle and connective tissues. Such a system would be parallel to the more superficial C-tactile afferent system of the skin.

Comments by Robert Schleip, PhD

I consider this new discovery as a very meaningful one for our field of manual therapies. It indicates that deep touch may not only foster similar important brain responses as does gentle superficial touch but that it also stimulates different brain regions in addition. We have learned in recent years how important the insula region is for interoceptive processing. The new observations, reported in this study, now indicates that deep touch seems to activate more the mid insular region, whereas gentle superficial touch activates more the posterior insula. In the common interoception model proposed by Craig, the subjective awareness of salient events is represented more anteriorly, whereas more sensory attributes are thought to be represented posteriorly (Craig 2009). While this understanding is currently shared by many authors in interoception research, it is important to treat it still as a hypothesis, rather than a proven fact. If verified, it might indicate that the deep touch, explored in this investigation, may have the potential of evoking a stronger feeling of salience, compared to a more superficial touch.

For me, this is a very nice complementation to the many recent research findings that heightened our respect for the potency of a gentle superficial touch. This included not only the important insights on the affective C-fibers and their insular connections but also the research findings about the much higher innervation density of superficial tissue layers compared with deeper ones (Fede et al. 2020). We knew from the work of Hoheisel et al. (2005) and others that there are unmyelinated nerve endings in deeper muscular tissues that are sensitive to innocuous levels of pressure. It will be intriguing to follow the continued research of the authors of the above article on deep touch and to learn more about the receptivity of these previously considered mysterious nerve endings and if/how they link with different insular functions.

Possibly this new research direction will enrich us with more specific insights, in which conditions – and for which functions – a more superficial touch tends to provide stronger healing effectiveness and for which conditions and functions a deeper and stronger touch may be more potent. And of course: if your clinical experience suggests a combination of both styles in many instances, my guess is that we may soon understand more exactly why and how that is the case.

References

Craig AD 2009. Nat Rev Neurosci 10:59–70

Fede et al. 2020. J Orthop Res 38:1646–54.

Hoheisel et al. 2005. PAIN Rep 4: e727.