Beyond the Brain – Decoding the Complexity of Chronic Pain

Chronic pain has become an increasingly prevalent health concern, affecting countless individuals and leading to disability and work-related absenteeism. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) recognizes chronic pain as a complex category comprising various pain conditions, sparking debate about whether it should be considered a distinct pathological condition or merely a symptom. Despite numerous medical interventions, the prevalence of pain disorders continues to rise, prompting a shift towards non-pharmacological treatments that promise cost-effective and improved quality of life outcomes.

Modern clinical guidelines for managing chronic pain now emphasize the importance of therapeutic education, structured physical activity, and cognitive-behavioural therapy. Pain neuroscience education, in particular, has gained traction by offering patients a comprehensive understanding of their pain, reducing fear-avoidance behaviours, and enhancing self-efficacy.

However, recent advances in cognitive neuroscience have led to a brain-centric view of pain, suggesting that the brain is solely responsible for pain perception. Phrases like “pain is an output of the brain” or “pain is an opinion of the brain” have gained popularity.

While there is some evidence supporting the link between brain activity and pain perception, it’s essential to avoid oversimplifying this multifaceted experience by attributing it solely to the brain. This reductionist perspective simplifies a complex human experience into the function of a single organ.

A review published in Journal of Clinical Medicine clarifies this Pain simplification.

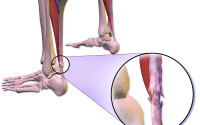

In reality, pain is a complex phenomenon influenced by multiple factors, including peripheral systems. Conditions like phantom limb pain and fibromyalgia were historically viewed through a brain-cantered lens, overlooking significant contributions from peripheral factors such as peripheral neuromas, ectopic discharges, and sensitization of dorsal root ganglia.

Peripheral systems are not the only players in the pain game; the immune system and hormonal variables also modulate pain activity.

Oversimplifying pain’s underlying mechanisms and may lead to inadequate treatment approaches. For example, pharmaceuticals targeting a single pathway may fall short, as seen with the controversial use of opioids and antidepressants in pain management.

While cognitive-behavioural approaches are crucial in pain management, they should not overshadow the importance of biomedical knowledge. Pain perception extends beyond cerebral interpretation and involves multiple bodily systems. Striking the right balance between these approaches is vital for effective pain management.

Pain neuroscience education has emphasized distinctions like “pain is not nociception” or “pain is not tissue damage.” While these distinctions simplify complex concepts, they risk becoming accepted truths without critical examination.

Pain is described as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience linked to actual or potential tissue damage, highlighting its subjective and individual nature. Nociception, on the other hand, refers to neural processes related to harmful stimuli, encoding their presence. Despite the distinction, terms like pain thresholds, pain processing, and pain fibres persist in scientific and clinical contexts, causing confusion.

Pain education often tends towards reductionism, relying on thought experiments and anecdotal evidence. However, the relationship between nociception and pain perception is not straightforward. Cognitive factors, emotional states, uncertainty, and other sensory inputs can influence pain perception. Therapeutic pain education may involve debates about language, as concepts that have been abandoned due to their nocebo effects may still serve a purpose in communication.

Understanding nociception involves recognizing the dynamic adaptability of the peripheral nervous system, the debate over the source of different pain experiences, the crucial communication between the immune and nervous systems, the role of the periphery in pain chronification, and the ubiquitous nature of nociception’s integration and modulation. This challenges a purely brain-centric view of pain, emphasizing the significance of peripheral contributions.

More recently pain awareness has been attributed to a possible specific neuromatrix composed of various brain regions. This so-called “Pain Neuromatrix” has sparked both support and scepticism in recent years.

This divide highlights the intricate nature of pain and its processing by our neural networks. Modern research suggests that pain perception is not limited to a single neural network but emerges from a multifaceted network responding to important sensory stimuli. This view underscores the key role of sensory stimuli in the pain experience. Additionally, innovative models like the Bayesian Model propose a novel perspective on pain, framing it as a probabilistic and inferential process, where perception is shaped not only by present sensory information but also by past experiences. The study of cortical processing and pain sheds light on the complex interaction between pain and consciousness. This understanding is crucial for guiding future research and holds significant potential for enhancing the clinical management of chronic pain.

In summary, the implications for manual therapy in the context of chronic pain involve adopting a holistic and individualized approach, considering both peripheral and central factors, collaborating with other healthcare professionals, and staying informed about the evolving understanding of pain mechanisms. By doing so, manual therapy can be an integral part of comprehensive pain management strategies for individuals dealing with chronic pain.