Form Closure, Force Closure & Myofascial Slings

The sacroiliac (SI) joints are now well-known and become popular as the source of lower back pain. Form Closure and Force Closure, which comes from the orthopaedic and physiotherapy literature are now quite popular in bodywork. This article attempts to describe these terms and its relationship to SI joints stability and contribution to lower back problem. This article is derived from the work by Craig Liebenson1 and Diane Lee2.

SI joints dysfunction has been proven to cause not only lower back pain, but also groin and thigh pain. For many decades, clinicians have been convinced the SI joints were not mobile, but this notion is not based on research findings. Especially in the last two decades, research has proven otherwise; mobility in the SI joints is usual, even in old age.

Movement in the SI joints and symphysis pubis is made possible by the fibrocartaligenous structure of these joints. It is both necessary and desirable that they move, so that they can act as shock absorbers between the lower limbs and spine, and to act as a proprioceptive feedback mechanism for coordinated movement and control between trunk and lower limbs.

As the SI Joints are capable of some movement, they must be controlled for effective force transfer to take place between trunk and lower limbs. The muscle system is able to provide a dynamic way of stabilising the sacroiliac joint.

The ability to effectively transfer load through the pelvic girdle is dynamic and depends on optimal function of the bones, joints and ligaments (form closure) , optimal function of the muscles and fascia (force closure), and appropriate neural function (motor control, emotional state).

The stabilization of the SI joints can be increased in two ways. Firstly, by the interlocking of the ridges and grooves on the joint surfaces (form closure); secondly, by compressive forces of structures like muscles, ligaments and fascia (force closure). Muscle weakness and insufficient tension of ligaments can lead to diminished compression, influencing load transfer negatively.

For therapists, ‘force closure’ is of greater interest because we can influence this through exercise and retraining.

FORM CLOSURE

The self-locking mechanism of the pelvis is called form or force closure. Form closure is a feature of the anatomy of the SI joints, mainly their flat surfaces, and promotes stability. Unfortunately, these flat surfaces are vulnerable to shear forces such as can occur during walking.

Since the SI joints have to transfer large loads, the shape of the joints is adapted to this task. The joint surfaces are relatively flat which is favourable for the transfer of compressive forces and bending moments. However, a relatively flat joint is vulnerable to shear forces.

The SI joints are protected from these forces in three ways. Firstly, due to its wedge shape, the sacrum is stabilized by the innominates. Secondly, in contrast to normal synovial joints, the articular cartilage is not smooth. Thirdly, the presence of cartilage-covered bone extensions protruding into the joint, the so called ridges and grooves. They seem irregular, but are in fact complementary, which serves a functional purpose.

This stable situation with closely fitting joint surfaces, where no extra forces are needed to maintain the state of the system, given the actual load situation, is termed ‘form closure’.

FORCE CLOSURE

If the sacrum could fit in the pelvis with perfect form closure, mobility would be practically impossible. However, during walking, mobility as well as stability in the pelvis must be optimal. Extra forces may be needed for equilibrium of the sacrum and the ilium during loading situations. How can this be reached?

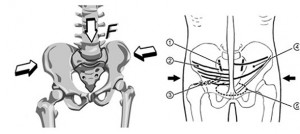

The principle of a Roman arch of stones resting on columns may be applicable to the force equilibrium of the SI joints. Since the columns of a Roman arch cannot move apart, reaction forces in an almost longitudinal direction of the respective stones lead to compression and help to avoid shear. For the same reason, ligament and muscle-forces are needed to provide compression of the SI joint. This mechanism of compression of the SI joints due to extra forces, to keep an equilibrium, is called ‘force closure’ (Figs. 1 & 2).

Figure 1. Transversely oriented muscles press the sacrum between the hip bones. This deep muscle corset forms lumbopelvic stability. (1) Sacoiliac joint. Muscles: transverse abdominal (2), piriformis (3), internal oblique (4), and pelvic floor (5).

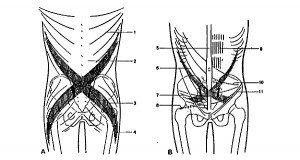

Figure 2. Trunk, arm and leg muscles that compress sacroiliac joint. The crosslike sling indicates treatment and prevention of lower back pain with stretngthening & coordination of trunk, arm and leg muscles in torsion & extension, rather than flexion. Posterior oblique sling Latissiumus dorsi (1), thoracolumbar fascia (2), gluteus maximus (3), iliotibial tract (4). Anterior oblique sling Linea alba (5), external oblique (6), transverse abdominals (7), piriformis (8), rectus abdominis (9), internal oblique (10), ilioinguinal ligament (11). Pictures from Pool-Goudzwaard et al.3.

MYOFASCIAL SLINGS

Andry Vleeming and co. proposed the concept of myofascial slings. The term ‘sling’ suggests, the myofascial system is able to provide a dynamic way of stabilising the SI joint through force closure. There are 3 slings that can provide force closure in the pelvic girdle include: the posterior oblique sling, the anterior oblique sling and the posterior longitudinal sling.

Posterior oblique sling: (Fig. 3) consists of the superficial fibres of the latissimus dorsi blending with the superficial fibres of the contralateral gluteus maximus through the posterior layer of the thoraco-lumbar fascia. The superficial gluteus maximus then blends with the superficial fascia lata of the thigh, in particular the superficial iliotibial band (ITB). This sling system runs at a right angle to the joint plane of the SIJ and in effect will cause closure of the joint when the latissimus and contralateral gluteus maximus contract. Furthermore, the gluteus maximus and thoracolumbar fascia have investments into the sacrotuberous ligament. Tension in this ligament will also cause closure of the SI Joints.

Anterior oblique sling: (Fig. 4) consists of the external oblique, internal oblique and the transversus abdominis via the rectus sheath, blending with the contralateral adductor muscles via the adductor-abdominal fascia. This will cause force closure of the symphysis pubis when contracted.

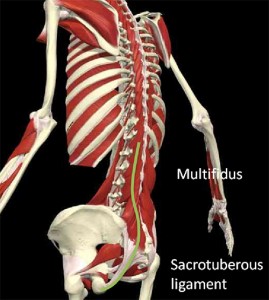

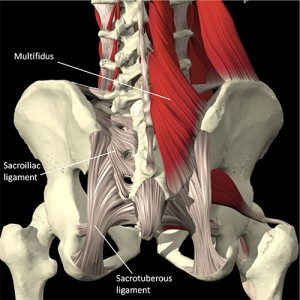

Longitudinal sling: (Figs. 5, 6) consists of the deep multifidus attaching to the sacrum with the deep layer of the thoracolumbar fascia, blending with the long dorsal sacroiliac joint ligament and continuing on into the sacrotuberous ligament. In a proportion of the population, the sacrotuberous ligament extends on to the biceps femoris muscle. This causes compression of the L5/S1 joint and compression of the SI Joints.

Note that the anterior and posterior oblique slings are similar to the Functional Front Line and Functional Back Line of Tom Myers’ Anatomy Trains.

MOTOR CONTROL2

Another important component for the stability of SI joints is motor control. Motor control addresses the nervous system and is about the co-ordination or co-activation of these deep stabilizers. One of the world’s leading research teams from the University of Queensland (Richardson, Jull, Hodges & Hides) have investigated the timing of these muscles in low back pain patients. They found that normally, these deep stabilizers should contract before load reaches the low back and pelvis so as to prepare the system for the impending force. They found that in dysfunction, there is a timing delay or absence of contraction of these muscles and consequently the system is not stabilized prior to loading. They also found that recovery is not spontaneous, in other words – the pain may go away but the dysfunction persists.

The Active Straight Leg Raising Test1

The active straightleg-raising test (ASLR) can be used to test which SI joint is unstable. It is useful for indicating effective load transfer between the trunk and lower limbs.

The test is as follows:

-Client lies supine with the legs about 20 cm apart.

-Actively lifts one leg 20 cm up following the instruction, ‘‘Try to raise your legs, one after the other, above the couch for 20 cm without bending the knee.’’

When the lumbopelvic region is functioning optimally, the leg should rise effortlessly from the table and the pelvis should not move (flex, extend, laterally bend or rotate) relative to the thorax and/or lower extremity.

The test is positive if

– the leg cannot be raised up

-Significant heaviness of the leg

– Decreased strength (therapist add resistance)

– Significant ipsilateral trunk rotation

Improvement should be noted:

– Manual compression through the ilia

– SI belt tightened around the pelvis

– Abdominal hollowing

Compression to the pelvis has been shown to reduce the effort necessary to lift the leg for patients with pelvic girdle pain and instability.

Treatment of SI joint dysfunction includes advice, soft tissue mobilization and exercise. Offer advice about lumbopelvic posture during sitting, standing, walking, lifting and carrying activities. In particular, give an advice to avoid creep during prolonged sitting. Also, a SI stabilization belt may be indicated until neuromuscular control of posture is reeducated subcortically.

Manual therapy to consider includes myofascial release of the lumbodorsal fascia and post-isometric relaxation of the adductors, piriformis, hamstrings, quadratus lumborum, iliopsoas, latissimus doris, erector spinae or tensor fascia lata.

Exercise should focus on reactivating the deep intrinsic stabilizers such as the transverse abdominus, internal oblique abdominals and multifidus muscles. The quadratus lumborum, gluteus medius, gluteus maximus and latissimus dorsi may also require endurance training. In particular, functional core exercises training stability patterns in movements and positions similar those of daily life, recreation and sport, or occupational demands.

For instance, squats, lunges, pushing and pulling movements.

Summary

The SI joints are an important source of pain. Force closure of the SI joints requires appropriate muscular, ligamentous and fascial interaction. The ASLR test can help to determine if a specific treatment is effective.

Advice about posture and support, manual therapy of related muscles and fascia, and exercise of key stabilizers are all important components in re-establishing lumbo-pelvic stability.

References

1 Craig Liebenson. The relationship of the sacroiliac joint, stabilization musculature, and lumbo-pelvic instability. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies (2004) 8, 43–45

2 Diane Lee. Myths and Facts and the Sacroiliac Joint. What does the Evidence Tell Us?

3 A. Pool-Goudzwaard, A. Vleeming, C. Stoeckart, C.J. Snijders and M.A. Mens, Insufficient lumbopelvic stability: a clinical, anatomical and biomechanical approach to “a-specific” low back pain. Manual Therapy 3 (1998), pp. 12–20.