Sedentary and Unhealthy Lifestyle Fuels Chronic Disease Progression by Changing Interstitial Cell Behaviour

Chronic diseases are responsible for a significant number of deaths worldwide, with ischemic heart disease being the leading cause of death. However, these chronic diseases are preventable through a healthy lifestyle, which includes regular physical activity, healthy eating, and stress management. Recent advances in physiology, such as understanding immune system interactions with food and the microbiome, intercellular cross-talk, and epigenetics, are beginning to address how unhealthy lifestyles cause chronic low-grade inflammation and how inflammation causes chronic disease progression.

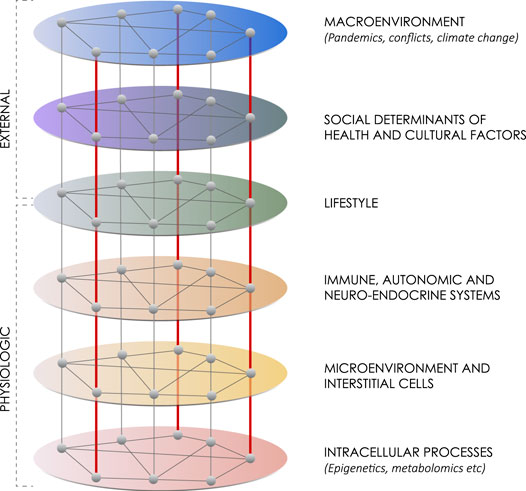

Dr Patricia Huston from Department of Family Medicine at University of Ottawa in Canada, presents a theory that an unhealthy lifestyle fosters chronic disease by changing interstitial cell behavior through a six-level hierarchical network analysis. The article is published in Frontiers in Physiology.

The top three networks include the macroenvironment, social and cultural factors, and lifestyle itself. The fourth network includes the immune, autonomic and neuroendocrine systems and how they interact with lifestyle factors and with each other.

The fifth network identifies the effects these systems have on the microenvironment and two types of interstitial cells: macrophages and fibroblasts. Depending on their behaviour, these cells can either help maintain and restore normal function or foster chronic disease progression. When macrophages and fibroblasts dysregulate, it leads to chronic low-grade inflammation, fibrosis, and eventually damage to parenchymal (organ-specific) cells.

This network diagram summarizes six layers of influences on maintaining health or advancing chronic disease. From Patricia Huston

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.904107

The sixth network considers how macrophages change phenotype.

(1) The larger macroenvironment,

Consisting of environmental and geopolitical factors, can greatly influence lifestyle and health. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic can have a profound impact on people’s health, with lockdowns leading to social isolation, stress, and decreased physical activity. Extreme weather events and political events like war, can also affect lifestyle and health.

(2) The social and cultural environment.

Social determinants of health and cultural factors play a significant role in shaping people’s lifestyle choices, and having economic stability and access to healthy activities, health services, and social support makes it easier to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Culture, family history, and social networks can also significantly impact lifestyle choices.

(3) Lifestyle

Generally healthy lifestyle include physical activity, diet, and psychological well-being. An unhealthy lifestyle may include stress, unhealthy diet, and sedentary behavior, leading to dysregulation and weight gain. In contrast, a healthy lifestyle includes regular physical activity, which can improve mood, memory, and executive functioning, leading to self-regulation and socialization.

(4) The Immune, Autonomic and Neuro Endocrine Network

The fourth network is the mesoenvironment that mediates between the macroenvironment and microenvironment. It includes three interacting regulatory systems of the body: the immune, autonomic and neuroendocrine systems.

The innate immune system plays a crucial role in maintaining health by responding to threats such as infections, trauma, or physiological stress. Dysregulation of the immune response leads to chronic low-grade inflammation, often driven by the macrophage. Macrophages are versatile cells that display multiple phenotypes and can switch between M0 (surveillance), M1 (inflammatory), and M2 (recuperative) states depending on the presence of threats or damage-associated molecular patterns. They release cytokines to signal for help and can consume microbes and cellular debris.

Food and physical activity have significant impacts on the immune system. A healthy diet and normal BMI foster a healthy microbiome, while an unhealthy diet high in carbohydrates and saturated fats decreases microbiome diversity and increases pro-inflammatory bacteria. Exercise has both direct and indirect benefits on the immune system by generating anti-inflammatory myokines and fostering a healthy microbiome. Sedentariness fosters inflammation and impairs the anti-inflammatory myokine response, leading to sarcopenic obesity.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) and immune system have integrated responses to perceived threats, but sustained sympathetic overdrive can disrupt the immune response. Good social experiences and psycho-social support stimulate the parasympathetic and neuroendocrine systems and create a buffering effect on stress and inflammation. Regular physical activity protects against upregulation of inflammatory cytokines and can dampen the sympathetic response. The microbiota-gut-brain axis, which involves communication between the microbiota, brain, and immune and autonomic systems, is influenced by diet and physical activity and can impact various diseases including metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease.

The neuroendocrine system involves the hypothalamic, pituitary, and adrenal axis, and other hormones that coordinate responses to stress and relaxation. A healthy lifestyle promotes a parasympathetic response and positive social interactions stimulate the release of oxytocin. Cortisol is released to calm inflammation, but chronic inflammation can lead to disease progression. Ghrelin increases appetite, creating a positive feedback loop, and leptin is associated with inflammation in obesity and metabolic syndrome. The regulatory systems interact through cytokines, biosignaling molecules, and neural stimulation.

Intercellular crosstalk is the primary method of communication between regulatory systems and immune/connective tissue cells in the microenvironment. Signalling molecules mediate both pro- and anti-inflammatory activities and are influenced by lifestyle changes in gut, brain, muscle, and fat. Crosstalk occurs locally and between tissues. Myokines released by muscle during exercise circulate and affect the brain, and interact with fat tissue. White adipose tissue generates cytokines, hormones, and growth factors that target peripheral tissues and are linked with metabolic syndrome. Crosstalk occurs in the microenvironment.

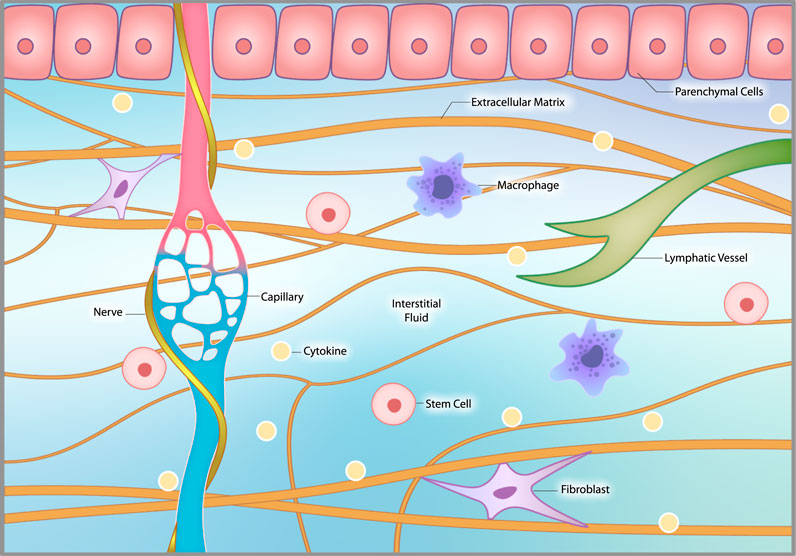

(5) The microenvironment, which refers to the microscopic conditions of a specific part of the body. The microenvironment includes the extracellular matrix (ECM), interstitial fluid, interstitial cells, and nerve fibers, and is responsive to local, systemic, and external influences. The interstitium is a complex and dynamic fluid-filled space that provides structure and support to organ parenchymal cells. Interstitial cells include macrophages and other immune cells, fibroblasts, stem cells, and other cells that vary by location.

Interstitial cells include macrophages and fibroblasts, which play a major role in both the normal healing process and chronic disease progression. Fibroblasts produce the ECM that provides the scaffolding of organs and tissues and play a central role in the maintenance and repair of virtually every tissue and organ in the body. Both macrophages and fibroblasts display tremendous plasticity, and can turn into various cell types depending on their microenvironment. Stem cells in the interstitium also exist, but not all have a regenerative capacity.

The interstitial microenvironment. The interstitium consists of extracellular matrix (ECM), interstitial fluid, interstitial cells and nerve fibers, including sympathetic nerves, that coil around local capillaries. The ECM provides structural support to organs and tissues. Interstitial fluid arises from the blood by diffusing out of capillaries. It circulates through the interstitium, interacts with interstitial cells and then is drawn into lymphatic channels and back into the venous circulation. Interstitial cells include macrophages, fibroblasts, occasional stem cells and other related cells that vary by location.

From Patricia Huston (2022)

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.904107

The healing process after injury or disruption consists of three phases: an inflammatory phase, a repair phase, and a remodelling phase. In the inflammatory phase, resident and circulating macrophages release pro-inflammatory cytokines to recruit cells and produce ECM to repair the damaged tissue. The repair phase involves anti-inflammatory cytokines, stem cell differentiation, angiogenesis, and matrix remodeling, while the remodelling phase involves realignment of the ECM with local tissue biomechanics. Fibroblasts play a major role in all three phases of the healing process.

Chronic low-grade inflammation occurs when the healing process gets stalled, often due to repetitive conditions or chronic insults that stimulate an inflammatory response. Unhealthy lifestyle factors like sedentariness, poor diet, and chronic stress can foster dysregulation of macrophages and fibroblasts, leading to tissue fibrosis and a vicious cycle of chronic inflammation and increasing tissue dysfunction. This pattern is seen in chronic diseases affecting various organs and tissues, where fibrosis is a hallmark of end-stage disease with no current treatment.

Understanding the network of factors that influence health can lead to a more proactive approach to wellness and contribute to the new concept of whole person health. Lifestyle can affect cell behavior and knowledge of this provides a physiologic basis for the emerging interest in salutogenesis, the process by which health is maintained and restored. Rather than treating each chronic disease separately by a focus on parenchymal pathology, a salutogenic strategy of optimizing interstitial health could prevent and mitigate multiple chronic diseases simultaneously.