Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome and Lower Limb Biomechanics

Hip joint impingement, better known as femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI or FAIS), is a movement-related condition, which is usually caused by abnormal bone formation of the femoral head and/or the acetabulum. The abnormal bone formation is often genetic in origin.

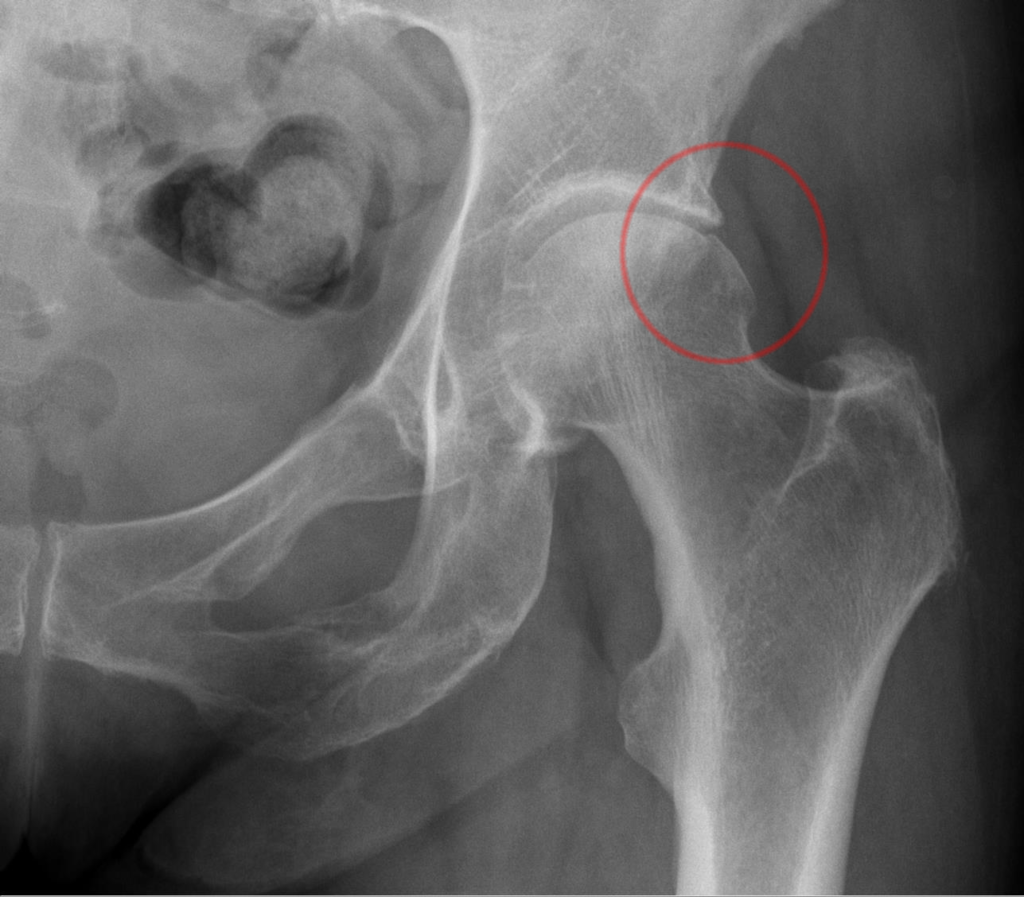

- When it occurs at the femoral head, it is termed a cam deformity (“cam” is short for “camshaft” referring to the egg-shaped, somewhat rounded-triangular-shaped femoral head that results; in other words, the shape of the femoral head not perfectly round).

- When it occurs at the acetabulum, it is referred to as a pincer deformity.

- When it occurs at both the femoral head and the acetabulum, it is referred to as mixed deformity.

The problem is that the abnormal shape of the femur and/or acetabulum does not allow for proper roll and glide of the joint surfaces along each other, hence impingement of the bones occurs during motion. This impingement often results in damage to the cartilaginous labrum of the joint or the articular (hyaline) cartilage of the joint. The poor mechanics will also likely lead to early degenerative osteoarthritic changes, which can result in calcium deposition bone spurs that further the impingement.

Diagnosis

Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome has a complex presentation of morphology, symptoms, and clinical signs. It often presents with hip pain, groin pain, stiffness, and/or restricted range of motion of the hip joint.

Diagnosis is usually made in two ways. Clinically, it is confirmed by reproduction of the impingement pain with certain characteristic movements, usually flexion, adduction, and internal (medial) rotation of the femur at the hip joint. In fact, reproduction of the characteristic pain of this syndrome with these movements is considered to be 90% reliable for the diagnosis to be accurate. Diagnosis is also made by X-Ray analysis (or other imaging technology) that demonstrates the abnormal bony shape. However, presence of the abnormal bony shape in and of itself is not diagnostic for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome; pain with movement must also be present for the diagnosis to be made. It is common for people with the abnormal bony shape to be symptom free. In fact, cam morphology has been reported in up to 60%–90% of athletic populations. However, the factors that delineate those who develop impingement symptoms and those who do not are unclear.

But mechanically, given the altered kinematics, altered bony shape would seem to be a predisposition for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome, with its concomitant signs and symptoms, to occur. When the characteristic pain of this condition is present with movement, confirmation by X-Ray is usually done.

Biomechanical Consequences

Since femoroacetabular impingement syndrome is a movement-related condition, biomechanical impairments associated with this condition may play a role in symptom development and persistence, as well as play a role in structural joint deterioration over time. In other words, clients with this condition will likely change their movement patterns in an effort to avoid the pain of the condition. These altered movement patterns may then, in turn, contribute over time to further functional and structural problems at the hip joint, let alone at other elements of the kinematic chain of the lower extremity.

Review Study

A review was conducted by researchers from Australia to identify differences in hip and pelvic biomechanics in patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome compared with controls during everyday activities such as walking and squatting. The studies that were investigated evaluated hip or pelvic kinematics and/or joint torques of everyday activities in patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome compared with the asymptomatic contralateral limb or a control group of healthy individuals. Fourteen studies were included (11 cross-sectional and 3 pre/post intervention), varying between low and moderate reporting quality.

The review found that patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome walked with a decreased range of motion of hip extension, internal rotation, and external rotation. They also squatted to a lesser depth. This review suggests that patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome may demonstrate hip biomechanical impairments during walking and squatting. At present, there is minimal literature available to comment on other tasks.

Comment by Joseph Muscolino

Although there is often a lag between structural deformity and functional impairment and/or pain (the human body can put up with quite a lot of structural change without necessarily having altered function or pain), any belief in the consequences of altered biomechanics would suggest that having a structural deformity would have some type of functional consequence, let alone pain. The results of this review study do show that people with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome, do have altered joint ranges of motion. Decreasing range of motion in any direction would by necessity decrease the stretching/lengthening of the tissues on the “other side” of the joint, for example, the antagonist musculature. This would likely lead to tighter/tauter tissues in time, that could then create further dysfunction (for example, fascial adhesion) and/or pain. Once an initial myo-fascio-skeletal dysfunction begins, compensations will inevitably occur, which will then create their own dysfunctions, which will then lead to their own compensations, etc., etc. For this reason, the best advice is always to try to avoid the initial occurrence of the problem in the first place, or address the issue as soon as possible once dysfunction or pain begins. The age-old saying “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” are words to live by.