Putting the Maximus Back into Gluteus Maximus

Putting the Maximus Back into Gluteus Maximus By John Gibbons

Manual therapists are what I call detectives: they possess some clues (patient’s history and symptoms), but they then have to take the patient through an elimination process (via a physical assessment) to hopefully find out and identify the actual underlying cause of the symptoms. The purpose of this chapter is to briefly explain about a patient who presented with pain in the left shoulder area, and to demonstrate that the possible cause of the problem can originate in an area that one might not consider in view of the patient’s presenting symptoms.

This article hopefully demonstrates what Dr. Ida Rolf states—“Where you think the pain is, the problem is not.” I want to illustrate this statement from Dr. Rolf with a case study taken from my own physical therapy clinic at the University of Oxford. As I become more experienced, not only in lecturing physical therapy courses but also as a practicing sports osteopath in my own clinic, I am convinced that many issues which patients and athletes present with are purely symptoms rather than actual causes.

The case study below is just a small snippet of the information that I provide in the Vital Glutes book. The information contained within the study is taken from a real case study patient who came to my clinic for a consultation.

Case Study

The patient in question was a woman of 34 and a physical trainer for the Royal Air Force. She presented to the clinic with pain near the superior aspect of her left scapula (Figure 1). The pain would come on four miles into a run, forcing her to stop because it was so intense. The discomfort would then subside, but quickly return if she attempted to start running again. Running was the only activity that caused the pain. Her complaint had been ongoing for eight months, had worsened over the past three, and was starting to affect her work. There was no previous history or related trauma to trigger the complaint.

After seeing different practitioners, who all focused their treatment on the upper trapezius, she visited an osteopath who treated her cervical spine and rib area. The treatments she had received were biased toward the application of soft tissue techniques to the affected area, namely the trapezius, levator scapulae, sternocleidomastoid (SCM), scalenes, and so on. The osteopath had also used manipulative techniques on the facet joints of her cervical spine—C4/5 and C5/6. Muscle energy techniques and trigger point releases were used in a localized area, which offered relief at the time but made no difference when she attempted to run more than four miles. She had not undergone any scans (e.g. MRI or x-ray).

Figure 1. Diagram of painful area—left superior scapula

Assessment

During a consultation (subjective history) the physical therapist will ask specific questions relating to the patient’s presenting pain so that a picture can be formed in their mind. This is a normal process in order for the physical therapist to come up with a hypothesis; this type of initial diagnosis will then help the therapist decide on what tissue(s) might be responsible for causing the client’s presenting pain/symptoms. For the patient in question, the potential tissues responsible for the pain to her superior scapula are:

- Upper trapezius

- Levator scapulae

- Scalenes

- Thoracic rib

- Cervical rib (extra rib forming from the transverse process of C7)

Once a subjective history has been conducted, the physical therapist then proceeds to an objective assessment: this is where the therapist uses specialized techniques to assess the musculoskeletal system to come up with a thorough diagnosis. One of the specific techniques employed by the therapist can be simple range of motion (ROM) tests that are initially performed by the patient; these are known as active range of motion (AROM) tests. This assessment is generally followed by a series of passive range of motion (PROM) tests; these tests are normally performed on the patient by the therapist, and are commonly used to check the integrity of the affected joint. Resisted testing comes next: this type of specific movement tests the power and involvement of the contractile tissues, i.e. muscles and tendons. The physical therapist also uses palpatory awareness through their fingertips to decide on the condition of the affected tissues, and will generally include special tests to complement the diagnosis.

The potential causes of my patient’s presenting pain are:

- Referral pain from cervical facet C4/5 or C5/6.

- Protective spasm/strain of upper trapezius or levator scapulae.

- Dysfunction of the glenohumeral joint or even the acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) or sternoclavicular joint (SCJ).

- Intervertebral disc bulge of C4/5 or C5/6.

- Elevated first rib.

- Cervical rib (extra rib from the transverse process of C7).

- Relative shortness/tightness of the scalenes.

- Positional—due to upper crossed syndrome related to a forward head posture and rounded shoulders caused by tight pectorals and SCM, and possibly weak rhomboids and serratus anterior.

- Upper lobe of left lung, referring to the trapezius.

- Diaphragm—this is innervated by the phrenic nerve, which originates from the level of C3–5 from the cervical spine; the dermatome from C3–5 can cause a referred pattern of pain that can radiate to the area of the shoulder (dermatome is an area of skin that is supplied from a single nerve root).

As you can see, there are many possible causes of the patient’s presenting pain. This list is not exhaustive and highlights just some of the many avenues to consider when confronted with a common complaint of “shoulder/trapezius pain.”

Taking a Holistic Approach

Let’s now assess the case study patient globally rather than locally, remembering that the pain only comes on after running four miles.

When I see a new patient for the first time, no matter what the presenting pain is, I normally assess the pelvis for position and movement, as I consider this area of the body in particular to be the “foundation” for everything that connects to it. I often find in clinic that when I correct a dysfunctional pelvis, my client’s presenting symptoms tend to settle down. However, when I assessed this particular patient, I found her pelvis was level and moving correctly. I then went on to test the firing patterns of the gluteus maximus (referred to as the Gmax for the remainder of this book), which I often do with patients and athletes who participate in regular sporting activities. However, I only test the firing pattern sequence once I feel that the pelvis is in its correct position; the logic here is that you often get a positive result of the muscle misfiring when the pelvis is slightly out of position.

With the patient in question, I found a bilateral weakness/misfiring of the Gmax, but the firing on the right side seemed a bit slower. As I had not found any dysfunction in the pelvis, I pursued this line of approach a little further.

Before we continue I would like to pose a few questions for you to think about:

- How does a weakness of the Gmax on the right side cause pain in the left trapezius?

- Is there a link between the Gmax and the trapezius, and if so, how is this possible?

- What can be done to correct the issue?

- What has happened to cause it in the first place?

To answer these questions, we need to look at the functional anatomy of the Gmax, and the relationship of the Gmax to other anatomical structures, as detailed in later chapters.

Gmax Function

The Gmax operates mainly as a powerful hip extensor and a lateral rotator, but it also plays a part in stabilizing the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) by helping it to “force close” while going through the gait cycle.

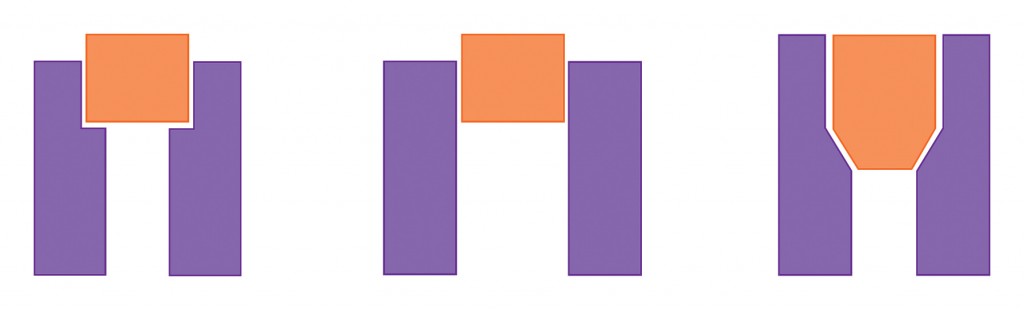

Some of the Gmax muscular fibres attach to the sacrotuberous ligament, which runs from the sacrum to the ischial tuberosity. This ligament has been termed the key ligament in helping to stabilize the SIJ. To gain a better understanding of this action, we first need to consider two concepts—“form closure” and “force closure”—which are both associated with stability of the SIJ (see Figure 2).

The shape of the sacrum—along with its ridges and grooves, and the fact that it is wedged between the ilia—helps to bring natural stability to the SIJ. This is known as form closure. If the articular surfaces of the sacrum and the ilia fitted together with perfect form closure, mobility would be practically nonexistent. However, form closure of the SIJ is not perfect and movement is possible, which means stabilization during loading is required. This is achieved by increasing compression across the joint at the moment of loading; the surrounding ligaments, muscles, and fascia are responsible for this. The mechanism of compression of the SIJ by these additional forces is called force closure.

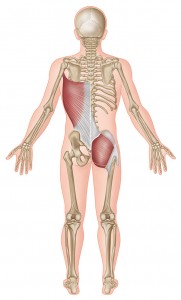

When the body is working efficiently, the forces between the innominates and the sacrum are adequately controlled, and loads can be transferred between the trunk, pelvis, and legs. So how do we link this to the patient’s complaint? In one of my previous articles (Gibbons 2008), about training the Oxford rowing team, I wrote about the posterior oblique “sling.” This structure directly links the right Gmax to the left latissimus dorsi via the thoracolumbar fascia (Figure 3). The latissimus dorsi has its insertion on the inner part of the humerus, and one of the functions of this muscle is to keep the scapula against the thoracic cage and aid in depression of the scapula.

Figure 2. Form closure and force closure.

Figure 3. Posterior oblique sling

Piecing It All Together

So what do we know? We know that the right side of the patient’s Gmax is slightly slower in terms of its firing pattern and that this muscle plays a role in the force closure process of the SIJ. This tells us that if the Gmax cannot perform this function of stabilizing the SIJ, then something else will assist in stabilizing the joint. The left latissimus dorsi is the synergist that helps stabilize the right Gmax and, more importantly, the SIJ. As the patient participates in running, every time her right leg contacts the ground and goes through the gait cycle, the left latissimus dorsi is over-contracting. This causes the left scapula to depress, and the muscles that resist the downward depressive pull will be the upper trapezius and the levator scapulae. Subsequently, these muscles start to fatigue; for the patient in question, this occurs at approximately four miles, at which point she feels pain in her left superior scapula.

Treatment

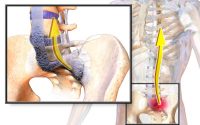

You might think the easy way to treat the weakness in the Gmax is to simply prescribe strength-based exercises. However, in practice this is not always the correct solution, as sometimes the tighter antagonistic muscle is responsible for the apparent weakness. The muscle in this case is the iliopsoas (hip flexor), and shortening of this can result in a weakness inhibition of the Gmax. My answer to this puzzle was to stretch the patient’s right iliopsoas muscle to see if it promoted the firing activation of the Gmax, while at the same time introducing strength exercises for the Gmax. All this will be explained in more detail in chapter 8 of the Vital Glutes book.

Prognosis and Conclusion

I advised the patient to abstain from running and to get her partner to assist in lengthening the iliopsoas, rectus femoris, and adductors twice a day. Strength exercises were also advised twice daily until the follow-on treatment (these exercises are discussed in later chapters). I reassessed her 10 days later and found normal firing of the Gmax on the hip extension firing pattern test, and a reduction in the tightness of the associated iliopsoas, rectus femoris, and adductors. Because of these positive results, I advised her to run as far as felt comfortable. I was not sure if my treatment was going to correct the problem, but she reported that she had no pain during or after a six-mile run. The patient is still pain free and continues to regularly use the Gmax strengthening exercises and the lengthening techniques for the tight muscles.

This case study demonstrates that very often the underlying cause of a condition or problem may not be local to where the symptoms/pain presents, which means that all avenues need to be fully considered. I hope that the information from this study has intrigued you enough to continue reading, as the information presented is just a taster of what is to come in the following chapters. Remember, this book is what I call a jigsaw puzzle journey—if you stick with it, the picture will eventually become a lot clearer.

This article is an extract from The Vital Glutes by John Gibbons. Reproduced here courtesy of Lotus Publishing. Text & Figures Copyright of John Gibbons.

JOHN GIBBONS is a qualified and registered osteopath with the British General Osteopathic Council, specialising in the assessment, treatment, and rehabilitation of sport-related injuries. Having lectured in the fields of sports medicine and physical therapy for over twelve years, John delivers advanced therapy training to qualified professionals within a variety of sports.