Altered patterns of pelvic bone motion determined in subjects with posterior pelvic pain

A summary of the study by Barbara Hungerford, Wendy Gilleard, Diane Lee. Published in Clinical Biomechanics (2004)

In our daily practice, we all encounter patients presenting with low back (hip / sacroiliac joint / SIJ pain), and there is no doubt that on-going low back pain results in a significant financial and economic burden to the health care system and society in general. In many instances low back pain is still poorly understood and not well managed, this is partly due to the medical profession’s dependence on costly imaging such as MRI scans and with an over-emphasis on only looking at the structure of the lumbar spine instead of evaluating the mechanics of the lumbar/ sacroiliac joints when addressing low back pain.

The spine instead should be considered as a fully integrated structure rather than only examining or treating the sensitive region. And what better place to start than at the base, in other words at the pelvis. Outside of the mainstream medical profession, there is a recognition of the importance of the pelvis and sacroiliac joints, but at the same time, there is also a lot of unnecessary confusion about how best to assess and treat the pelvis.

A study by Barbara Hungerford, Wendy Gilleard, Diane Lee, published in Clinical Biomechanics (2004) aimed to determine altered patterns of pelvic bone motion in subjects with posterior pelvic pain using skin markers.

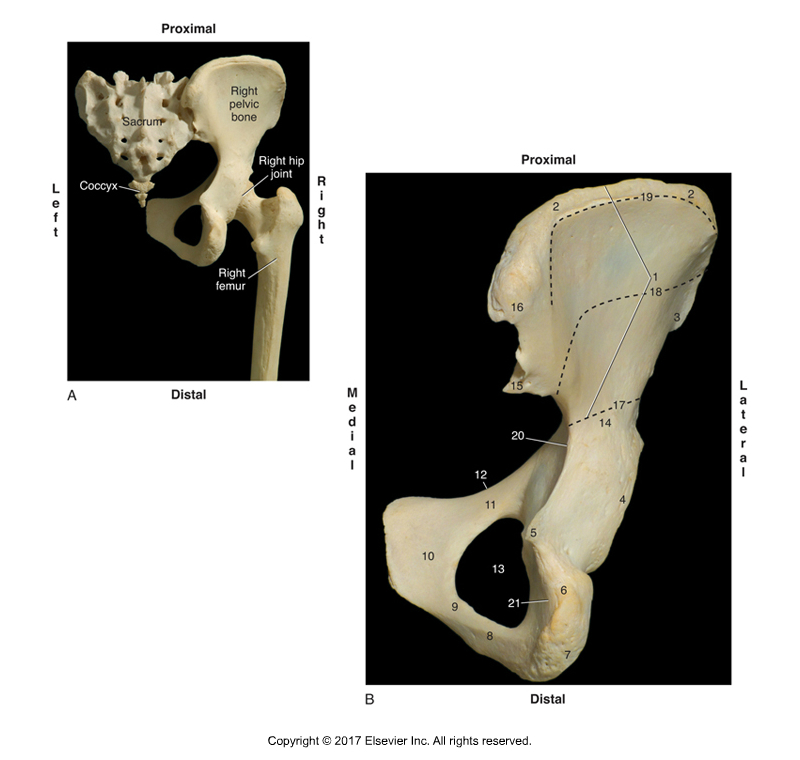

Lumbar spine and pelvis

A primary function of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joints of the pelvis is to transfer the loads generated by body weight and gravity during standing, walking, and sitting. During weight bearing activities, control of intra-pelvic motion (motion between the sacrum and ilium of the pelvic bone (innominate bone) is required for the transference of loads between the spine and the lower limbs. According to Panjabi (1992) stability is achieved when the passive, active, and control systems work together to produce an approximation of the joint surfaces.

The ability to effectively transfer load through the pelvis is dynamic and therefore depends on:

- Optimal function of the bones, joints, and ligaments,

- Optimal function of the muscles and fascia, and

- Appropriate neural function.

For every joint, there is a position of maximum stability called the self-braced (close-packed) position in which there is a maximum congruence of the articular surfaces and maximum tension on major ligaments. In this position, the joint is under significant compression, and the ability to resist shear forces is enhanced by tensioning of the passive structures and increased friction between the articular surfaces. The close-pack position of the sacroiliac joint is nutation (anterior tilt rotation) of the sacrum relative to the ilium (which is relatively the same as posterior tilt rotation of the ilium relative to the sacrum).

Posterior view of the right sacroiliac joint. Figure credit: Muscolino, Kinesiology – The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3rd Edition, 2017, Elsevier.

The study

A study by Barbara Hungerford, Wendy Gilleard, Diane Lee, published in Clinical Biomechanics (2004) aimed to determine altered patterns of pelvic bone motion using skin markers in subjects with posterior pelvic (sacroiliac) pain.

A cross-sectional study of three-dimensional angular and translational motion of the ilium relative to the sacrum in two subject groups. Fifteen lightweight highly reflective 15 mm diameter balls were used to define the bony landmarks of each innominate, femoral segments, and the sacrum. A 6-camera motion analysis system was used to determine 3D angular and translational motion of pelvic skin markers during standing hip flexion.

Fourteen males with sacroiliac pain and healthy age and height matched against fourteen controls (with no sacroiliac pain) were studied. Each subject in the sacroiliac pain group reported unilateral pain over the posterior pelvic/SI region for greater than two months and no pain above the lumbosacral junction. The pain was consistently and predictably aggravated by activities that vertically loaded the pelvis (walking, standing, or sitting).

Positive results on the side of posterior pelvic pain in clinical tests for impaired lumbopelvic stabilization were looked for with the following three tests:

Active Straight Leg Raise Test: The supine patient was asked to actively flex the thigh at the hip joint while keeping the knee joint in full extension. A positive test was indicated when the pelvis failed to remain in neutral alignment, and the subject reported difficulty or inability to elevate the lower extremity.

Standing Hip Flexion Test: During a left standing hip flexion test, the subject stands on one limb and flexes the other thigh at the hip towards 90⁰. The ilium on the thigh-flexion side should posteriorly rotate relative to the sacrum, thereby dropping the PSIS (posterior superior iliac spine) relative to the sacrum. Further, the ilium on the support-limb side should also posteriorly tilt as well. A positive test was indicated when either PSIS was found to remain in a superior position relative to the sacrum, in other words, the ilium did not drop into posterior tilt.

Joint Play Motion Palpation Test: This test was used to evaluate motion of the SIJ. In this test, the ilium was challenged with manual pressure to glide relative to the sacrum.

Results

Active Straight Leg Raise Test: No differences were found between the pain and control groups.

Standing Hip Flexion Test: During the hip flexion component of the standing hip flexion movement, there was no significant difference in the patterning of translational motion between groups on the side of hip flexion. Posterior rotation of the ilium occurred with hip flexion in control subjects and sacroiliac pain subjects.

However, on the support-limb side, a significant difference in sacroiliac joint motion was found between subjects in the control group and subjects in the sacroiliac pain group. In the control group, posterior rotation of the weight bearing ilium occurred on the side of single leg support. However, in the sacroiliac pain group, anterior rotation occurred on the symptomatic support-limb side. In other words, on the support-limb side, the ilium rotated posteriorly in control subjects and anteriorly in symptomatic subjects.

Joint Play Motion Palpation Test: All subjects in the sacroiliac pain group demonstrated asymmetric stiffness of the SIJ when the innominate was challenged to glide relative to the sacrum, as compared to the control group.

In summary, on the supporting leg, the innominate rotated posteriorly in controls and anteriorly in symptomatic subjects.

Conclusion

Posterior rotation of the ilium, as measured using skin markers during weight bearing in controls may reflect activation of optimal lumbopelvic stabilization strategies for load transfer.

Anterior tilt rotation occurred in subjects in the pain group. Anterior tilt rotation of the ilium is not the stable close-pack position of the SIJ and this suggests a failure to stabilize intra-pelvic motion for load transfer. This is a non-optimal pattern and may indicate abnormal articular or neuromyofascial function during increased vertical loading through the pelvis. Further, joint play motion palpation of the symptomatic SIJ was found consistently in the pain group subjects.

Relevance

This study found that posterior rotation of the hip bone occurred during weight bearing in controls. This movement pattern is thought to optimise stability of the pelvic girdle during increased loading. Conversely, anterior rotation occurred in symptomatic subjects during weight bearing. This is a non-optimal pattern and may indicate abnormal articular or neuromyofascial function during increased vertical loading through the pelvis.

Taso Lambridis will present Demystifying the SIJ & Pelvis workshop in Sydney ,17-18 Nov 2018. For more information, visit www.terrarosa.com.au

Why another SIJ and pelvic course?

Over the past 15 years there has been a continued interest and research into this often complex region however there are still many unanswered questions regarding the fundamental function and role of the SIJ. There is an ongoing debate on what if any role the SIJ plays in the cause of low back pain as well as continued controversy about how best to treat SIJ or pelvic problems.

Taso has been running his SIJ series of courses since 2010 and presents a comprehensive 2 day course aimed at enhancing your understanding of this key region of the body. For more information, visit www.terrarosa.com.au

Taso Lambridis is a highly skilled Physiotherapist from South Africa with over 20 years experience treating musculoskeletal and sporting injuries. He has gained extensive experience having worked internationally and his clinical area of expertise is treating complex lumbar spine and pelvic injuries.

Taso has a post-graduate MSc Sports Medicine degree from the UK and has worked in elite physiotherapy and sports clinics in London where he treated professional rugby players, English Premiership football players, elite triathlete and runners as well as dancers from London’s leading West End theatre shows, dance academies and schools for the performing arts.