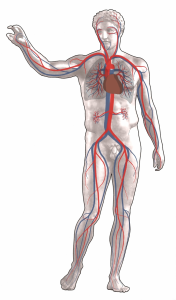

Can massage increase blood circulation?

An increase in blood circulation to muscle tissue is one of the most promoted positive effects of massage. One reason for this is that improved blood circulation is supposed to deliver more oxygen and other nutrients to the muscle tissue. For example, a 2017 research study demonstrated a positive relationship between an increase in blood flow and performance recovery between bouts of high-intensity exercise. Some trials have been carried out to investigate the effect of massage on blood flow, but the results are inconclusive and conflicting. There is also a myth propagated via the web that massage cannot increase blood flow. So what research really says?

Difficulty Measuring Blood Circulation

According to Niki Munk, LMT from the Indiana University, the problem with addressing blood flow changes in muscle tissue or in any tissue is a methodology issue, i.e., how blood flow is measured. A review paper published in 2005 showed that there are conflicting results on the effect of massage on blood flow; the outcomes depend on measurement techniques.

While this might seem easy enough, measuring so-called “muscle hemodynamic” properties is not straightforward. Most studies, which investigated the effect of massage on blood flow, do not directly measure the change in blood flow; rather, they inferred it from the arterial width, blood velocity, or skin temperature.

Doppler Ultrasound

Some studies measure the effect of massage (usually in the lower extremities) on arterial blood flow using the Doppler Ultrasound instruments. The Doppler Ultrasound measures changes in large arteries and veins. However, this method is not sensitive to blood flow in the smaller vasculature, such as the capillary beds, thus this method measures blood velocity only in macro-regions rather than in specific muscle tissue.

Doppler Ultrasound Studies:

- A study from the University of Illinois recruited 36 sedentary young adults that were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: (1) exertion-induced muscle injury and massage; (2) exertion-induced muscle injury only, and (3) massage therapy only. Results showed that only groups #1 and #3 in which massage was done, increased brachial artery flow-mediated dilation compared to baseline.

- Two studies by the research group in the University of Waterloo, Canada used Doppler Ultrasound to monitor average blood flow. In one study, a certified massage therapist performed massage on ten healthy individuals on the forearm or quadriceps, and the results showed no change in brachial or femoral artery blood flow.

- In another study, daily (for four days) massaging of the quadriceps femoris musculature of one leg on subjects who had previously completed an intense bout of eccentric quadriceps work with both legs. Massage of the quadriceps muscles did not significantly elevate arterial or venous average blood velocity above resting levels, while gentle quadriceps muscle contractions did.

- A study by Hinds et al. from the UK recruited 13 male volunteers in three 2-minute bouts of concentric quadriceps femoris exercise followed by two 6-minute bouts of deep massage or a control (rest) period. Massage did not change femoral artery blood flow, but skin blood flow did increase.

- A study from Queen’s University, Canada, looked at 12 subjects that performed two minutes of strenuous isometric handgrip exercise followed by either massage, active recovery, or passive recovery. They found greater forearm blood flow in the active and passive recovery groups than in the massage therapy group.

- A study from Germany assessed the effect of foam rolling on the lateral thigh. Results from 21 healthy participants showed that arterial blood flow of the lateral thigh increased significantly following foam rolling exercises compared to baseline.

- A 2017 study from Japan examined friction massage on the popliteal fossa for 15 healthy male university students found increased blood flow velocity after friction massage. They indicated that friction to the popliteal fossa enhances venous flow by increasing the blood flow velocity in the popliteal vein.

- A study from Thailand evaluated Massage combined with Lumbopelvic Stability Exercises for people with low back pain and found tissue blood flow on the lumbar region increased following treatment.

The relationship between muscle contraction and blood flow was examined in a 2005 study. The researchers measured leg blood flow during increasing contraction intensities and partitioned flow into that during contraction versus relaxation. They demonstrated that there are impairment effects to blood flow during contraction (i.e., mechanical compression of muscle resistance vessels) and enhancement blood flow during relaxation. At the lightest work rate, the muscle pump had a net positive effect on muscle blood flow, while during steady-state moderate exercise the net effect of rhythmic muscle contraction was neutral, i.e., the blood flow impedance due to muscle contraction was offset by the potential enhancement during relaxation. At the higher work rates tested, any enhancement to flow during relaxation was insufficient to compensate the contraction-induced impedance to muscle perfusion.

Doppler Flowmetry

A study from Portugal tested application of massage in two directions: from ankle to knee and a reverse direction from knee to ankle in 16 healthy subjects. A 5-minute massage was applied on one knee while the other knee served as the control. Local microcirculation blood flow was measured using laser Doppler flowmetry. The results showed that both directions of massage increased surface blood flow. It is interesting to note that the study showed that of both treated and resting (control) limbs showed increased blood flow.

Tomography

A unique study from the UK measured blood flow on the brain using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) which requires injecting intravenous cannula. The study with 5 participants showed blood flow brain activation changes. Another study from Japan used positron emission tomography (PET) to measure blood flow in regions of the brain. They showed that subjects just under the prone condition showed an increase in cerebral blood flow compared to under supine condition. Light massage on the back further mediates the autonomic nervous system of comfortable sensation.

Hemoglobin concentration

Hemoglobin (Hb) is the protein in red blood cells that functions to deliver oxygen to the tissues, and thus it is a good measure of tissue oxygenation. A 2019 study tested the effect of Sequential Pulse Compression (instrument that delivers compression on the legs). 34 participants were randomly assigned to compression treatment or control. Compression significantly increased total hemoglobin and and oxygenated hemoglobin compared with the control condition.

Skin temperature

Many studies measure skin temperature, as skin rubbing or friction can produce local heating and hyperaemia within the rubbed area. The local rise in skin temperature theoretically indicates an increase in blood flow to the area. Massage has been shown to increase skin temperature in neck and shoulder, shoulder calf, and legs. However, this temperature effect is only temporary, and the temperature rise was not found in deeper muscles (2.5 cm from the skin surface).

Surface Blood flow

Studies which measured blood flow on the skin mostly agree that massage increased surface blood flow on toes and legs, lumbar muscles, and others.

A study from Portugal tested application of massage in two directions: from ankle to knee and a reverse direction from knee to ankle on 16 health subjects. A 5-minute massage was applied on one knee while the other served as a control. Local microcirculation blood flow was measured using laser Doppler flowmetry. The results showed that both direction of massage increased surface blood flow of both treated and resting (control) limbs.

Even mechanical massage using compressed air or air cuffs on legs also found to increase leg’s peripheral blood flow.

A study from Japan found that a 5-minute massage significantly increased facial skin blood flow in the massaged cheek for at least 10 minutes after the massage. In another experiment, a 5-week daily use of facial massage roller on the cheek significantly increased the vasodilatation response to the heat stimulation.

Albert Moraska from the University of Colorado in a review commented that collectively, in the smaller draining vasculature, massage appears to effectively increase movement of chemicals, but may have a lesser effect on large blood vessels.

Near Infrared Spectroscopy

Niki Munk and researchers from the University of Kentucky proposed the use of new technology with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIR) which can non-invasively measure dynamic information on oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin concentrations, total hemoglobin concentration, and blood oxygen saturation in deep tissue. The authors demonstrated the used of this instrument to evaluate the effect of massage on muscle microcirculation. Immediate increase in calf muscle relative blood flow (from 100 to 142%) was found following 8-min lower limb massage on a 28-year-old woman.

In a separate study from 2017, the NIR spectroscopy method was used to compare the acute effects of myofascial techniques and Kinesio Tape on blood flow at the lumbar paraspinal musculature. The results showed that myofascial techniques increased peripheral blood flow at the paraspinal muscles in healthy participants compared to kinesio tape and sham TENS application.

A 2006 study examined the effect of mechanical lumbar massage units during a 1 h simulated driving task. NIR measures showed that massage (delivered by aninstrument) increased of muscle oxygenationand muscle blood flow (compared to control) and also increased skin temperature.

A 2016 study from Japan examined friction massage on the popliteal fossa for 15 healthy male university students and found larger oxygenated hemoglobin after friction massage.

Despite of the conflicting studies, it seems that massage can increase surface blood circulation. However, it is still unclear the benefits of such effect and how it contributes to the overall positive aspects of massage.

Muscle pump

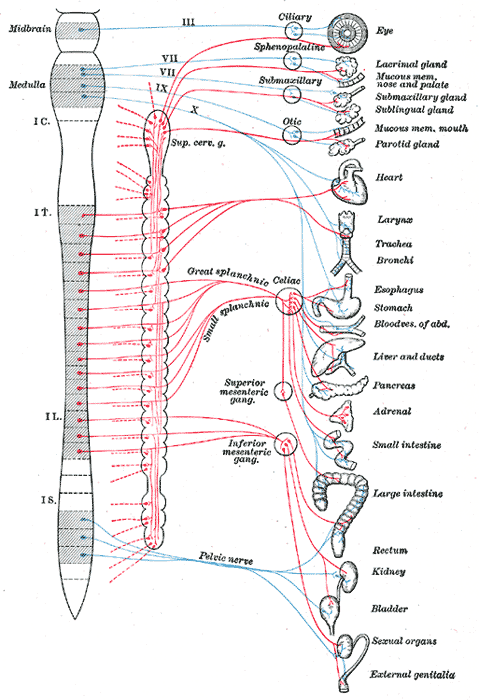

There is also a myth that blood flow is only controlled by heart. However, skeletal muscle can also aid in blood circulation, especially important in increasing return of low through the venous flow. Skeletal muscle contraction is also called a “second heart” and causes a rapid (within seconds) increase in skeletal muscle blood flow. A couple of mechanism has been proposed. The first is muscle pump.

Several experiments have been conducted to verify the muscle pump mechanism. The following is summarised by Joyner and Casey (2015)

Tschakovsky et al. (1999) developed a cuff system that rhythmically squeezed the forearm while they measured brachial artery blood flow. The compression pattern and pressures generated by the external cuff were designed to mimic the pressures generated by the contracting muscles. When the forearm was at or above heart level, this rhythmic “pumping” of the forearm caused little increase in brachial artery blood flow. In contrast, when the arm was below heart level, there were modest increases in blood flow with rhythmic cuff pumping of the forearm. This is consistent with the idea that full but not empty veins can contribute to the hyperemic responses to exercise.

A 2012 study recruited 12 healthy individuals who performed 3 min of standing plantar flexion exercise. Three conditions were tested: no applied compression, compression on the lower limb during the exercise period only, and compression during 2 min of standing postexercise recovery. The results showed that intermittent compression applied during exercise and recovery from exercise results in increased limb blood flow,

Blood circulation is primarily regulated by nervous system control of the heart and/or direct health of the heart itself. However, to the extent that blood flow circulation is a mechanical process in the peripheral tissues, a mechanical treatment method such as soft tissue manipulation, in other words, massage, should be able to affect it.

This is especially true of venous flow and lymphatic flow because they are not “directly related” to heart function. Venous and lymphatic circulations are based on the “muscular pump” in which muscle contractions physically compress venous/lymphatic vessels, causing a mechanical flow back toward the heart.

However, the focus of this blog post article and the studies mentioned herein is to measure the effect of massage on arterial blood circulation. Again, given that there is a component of arterial circulation that is mechanical, after all, blood flow is technically a mechanical process, then it would make sense that massage would be able to affect arterial flow. The mechanism for the ability of massage to increase arterial blood flow could be that it increases venous and lymphatic flow back to the heart, which then increases fluid in the system, thereby increasing blood pressure and therefore arterial blood flow. It is also possible that massage milks the fluid through the arteries, which then increases the draw from the capillary/venous end of the circulation. And perhaps the increased arterial circulation is due to a neurological stimulus of some kind in response to the work on the peripheral myofascial tissues. Or perhaps, it is due to another factor, or a combination of all of these factors plus more.

Regardless of the underlying mechanism, there seems to be a growing number of studies that do show a correlation between massage therapy and arterial circulation. Although these studies at present seem to be inconsistent in their findings, the fact that many of them do show a causal relationship is encouraging. There does seem to be sufficient evidence, and mechanically it does makes sense, to be able to claim that massage can have a beneficial effect on arterial blood flow, and therefore circulatory health. We certainly look forward to further studies on this subject.