Cerebrospinal fluid washes the brain during sleep

Sleep is vital for our health and wellbeing. Now, researchers at Boston University in Massachusetts found that during sleep, the cerebrospinal fluid flows in and out of the brain like waves, which could help clear metabolic wastes.

The study published in the Nov 2019 issue of Science journal, scanned the brain of 13 participants while they sleep using an MRI. The MRI allows the researchers to see the activity of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain during sleep.

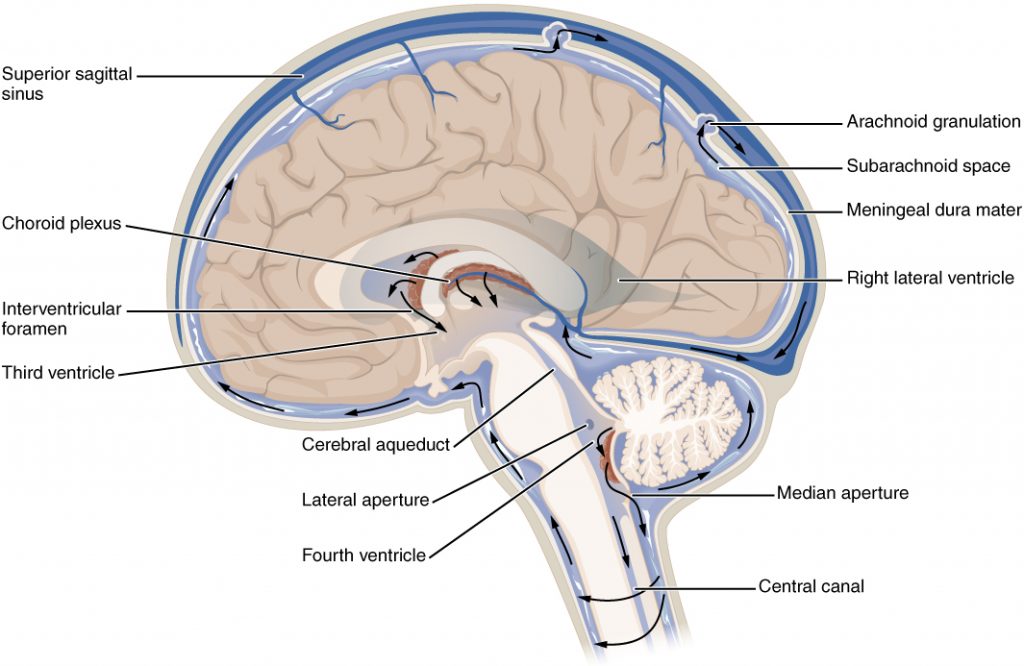

There are several stages of sleep. Sleep starts with a light form of slow-wave sleep (SWS), progresses to deeper SWS, and then shallow SWS, and concludes with REM sleep before beginning a new cycle. During SWS, the blood flow to the brain is reduced by 25%, which lowers cerebral blood volume by 10%. The study shows that this reduction in blood volume in the human brain allows inflow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to the third and fourth ventricles, which are fluid-filled cavities in the central brain. These waves may facilitate communication between fluid compartments and clearance of waste products.

There is a pattern of coupled low-frequency oscillations in the brain, blood oxygenation, and CSF flow during slow-wave sleep. Neural slow waves are followed by blood flow out of the brain, which in turn followed by CSF flow. The CSF waves occur about once every 20 seconds, providing physiologically restorative effects. The authors hypothesised that when the neurons shut off, they don’t require as much oxygen, so blood leaves the area. As the blood leaves, pressure in the brain drops, and CSF flows in to maintain the pressure.

Perhaps methods that aim to enhance cerebrospinal fluid movement, such as craniosacral therapy has some merits in people with sleeping difficulty and Alzheimer’s disease.

As a practitioner, having confidence in our therapeutic narratives has well-documented benefits, for both practitioner and client. So it’s natural to look to science to validate or bolster what we already believe works. (“Here’s proof of why clients sleep better after my cranial treatments!”)

But as an alternative, why not build both mental adaptability and conceptual accuracy by looking at this, and similarly interesting research findings, as possible inspiration for our hand-on work—ideas to metaphorically inform and excite our imaginations and our hands—rather than as proof or validation of our preferred therapeutic narratives (which of course, they’re not).

And what do we tell our clients we’re doing? “Imagining good things.” – Til Luchau