Does Carrying a Backpack Cause Back Pain in Children and Teenagers?

A recent study concluded that adolescent back pain and back pain in children is not associated with carrying a backpack, Dr Joe Muscolino critically unpacked the reasoning of such a research.

Children and adolescents commonly report back pain. Research shows the prevalence of complaints by the end of adolescence reaches levels comparable with adults. There is also evidence that having adolescent back pain predicts having back pain as an adult.

However, a recent study concluded that adolescent back pain and back pain in children is not associated with carrying a backpack. The systematic review by Australian researchers was published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (BJSM). The authors reviewed prospective cohort studies, cross-sectional and randomized controlled trials conducted with children or adolescents. Outcomes looked at in these studies were an episode of back pain, absence of school due to back pain, and an episode of seeking out care/treatment.

Comment by Joseph Muscolino

A “systemic review” study is also known as a “metastudy” (“meta” is Greek for “after”: think “metamorphosis” – “after” the “shape” [morphos means shape] of the caterpillar is the shape of the butterfly). These review metastudies have value, but are weak when it comes to drawing any type of definitive conclusion. This is because the focus of each of the individual studies is probably not the same as the focus of the other studies. And therefore, most all the other factors of each of the studies were probably not consistent, including such parameters as how the study was conducted, what factors were considered, what questions were asked, etc., etc. Yet, all these studies are grouped together, attempting to draw a specific conclusion. So why are metastudies conducted? Largely because they are inexpensive to carry out. Carrying out studies with large numbers of individuals in treatment and sham groups requires a tremendous amount of time, effort, and money. A metastudy only requires sitting down and sifting through and reading many studies and coming up with a conclusion. This is not to say that a fair amount of time is not needed, but it is inexpensive. And for researchers who live by the “publish or die,” they can be very attractive. And, as mentioned here, another problem is that their conclusion can be quite subjective. All this should be kept in mind when evaluating how much reliability should be placed on their conclusions, quite an important factor given that reliability and reproducibility are the major purposes of research studies.

Cross-Sectional and Prospective Studies

The studies were cross-sectional and prospective. A cross-sectional study is on in which a survey is taken at a single point in time and then used to compare characteristics between specific groups of people. A cross-sectional study is considered weaker evidence than a prospective study, which follow individuals over time. By far, most of the studies reviewed, 69 of the 74, were cross-sectional (these 69 studies involved a total of 72,627 individuals). The other five studies were prospective.

Cross-Sectional Studies’ Results

Among the cross-sectional studies, four found that a heavier backpack was associated with reports of back pain, three showed the method of carrying the backpack was related to pain, and three found carrying a bag for longer periods was related to having pain. One study found that 75% of students who had back pain reported that carrying their bag aggravated their pain. Therefore, 11 of the 69 cross-sectional studies linked adolescent back pain with carrying a backpack; 58 did not link adolescent back pain with carrying a backpack. Eleven out of 69 equates to 16%.

Prospective Studies’ Results

Of the five prospective studies, only two measured backpack weight and both found it was not associated with reporting back pain. Two studies found that the perceived weight or reported difficulty carrying the bag was associated with back pain for kids aged 9 to 14 years. The fifth study didn’t report any variables about backpacks. But in a question posed to adolescents (mean age of 15 years) with back pain asking what aggravated their pain, carrying their backpack was not mentioned. Hence, two of the five prospective studies did seem to link adolescent back pain with carrying a backpack; two out of five equates to 40%.

However, the authors indicated that the findings from the prospective studies were limited. This is because identifying risk factors for back pain wasn’t the primary aim of these studies, so the measurements used and the timing of data collection may not have been optimal for establishing causal relationships.

Authors’ Conclusion

Based on the aggregate of all the results they did have, the authors concluded that the there is no convincing evidence that aspects of schoolbag use increase the risk of back pain. For someone who has back pain, it may seem it worsens when carrying a heavy bag or carrying it on one shoulder, but it’s unlikely the backpack was the cause of the initial pain. Hence, the authors concluded that there is no convincing evidence that aspects of backpack use increase the risk of adolescent back pain in back pain in children.

Comment by Joseph Muscolino:

Warning, major Soapbox Speech ahead…

Oh my… I usually try to restrict my writing to content, but in this case, the problem is so much more fundamental. It is related to how we think…

So… I find it so distressing to read these studies and think about how they might influence public opinion and the opinion of health care practitioners. I hate to be one to criticize the value of research because I am such a big fan of research, but I am a fan of research studies that are carried out well, and that have reasoned well thought-out conclusions. Much of my problem lately is the big pendulum swing toward everything being “evidence-based,” which means that the conclusions that we make and how we use those studies to determine manual and movement therapy care must be “evidence based,” in other words based on research studies. This sounds so good, doesn’t it? But this push has largely prompted many individuals to shut off their brains and stop critically thinking and instead just read conclusions from research studies like this.

What are some of the problems with this study and its conclusions?

- It is a review metastudy, which by definition is inconsistent and weak when it comes to a conclusion (as I stated above).

- The authors admit that many of the studies were not really designed to make a conclusion about the relationship between adolescent back pain and carrying a backpack. And they admit this about the stronger type of study considered, the prospective studies.

- Eleven per cent of the cross-sectional studies and twenty per cent of the cross-sectional studies DID show a relationship between adolescent back pain and carrying a backpack. If we happened to have read any one of those studies, we would have walked away from it concluding that there IS a relationship between the two.

- In many cases, there was not evidence of the causal link between adolescent back pain and carrying a backpack, but the lack of proof of a conclusion is not the same as the conclusion being wrong. For example, to choose a silly example, there is no proof that dropping a two-ton weight on a giraffe would cause the giraffe back pain or injury because the study for this has not (yet?) been done. Therefore, one could make the following statement: “There is no proof that dropping a two-ton weight on a giraffe would cause injury to the giraffe!” Someone reading this statement might come away with the thought that dropping two-ton weights on giraffes, and perhaps other animals, is perfectly fine and healthy. After all, there is no proof of it causing harm, is there?

- The statement that usually describes this error in thinking is: “The absence of evidence is not evidence of the absence.”

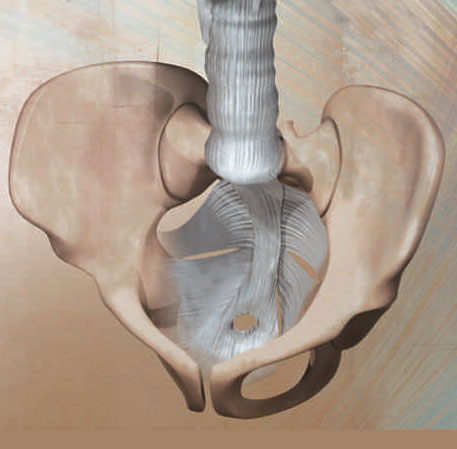

- The conclusions from this metastudy do not consider mechanics. I realize that with another swing of the pendulum too far, pain science advocates seem to be negating that mechanics can ever have anything to do with pain or dysfunction, but this swing of the pendulum is so far from reality that it boggles the mind. Let’s take an extreme example of this topic and see if it holds up. If the backpack were to weight, three hundred pounds, wouldn’t it clearly cause back pain? If so, how about two hundred pounds? If so, how about one hundred or eighty or whatever number you want to choose. At some point use become overuse becomes misuse becomes misuse, as Leon Chaitow likes to say. The point is that every tissue has a limit to the physical forces that it can tolerate. So there must be some effect of carrying around a backpack, at least at some point in its weight. And if it is slung over one shoulder, then the constant elevation of the shoulder girdle to keep it from falling off, even if the backpack were empty, would have to become a problem if the backpack is carried around too much. At some point, mechanics have to matter. Reading the conclusion to this research review would make someone think that they would not at all, ever.

- And perhaps the biggest problem I have with this study is the fact that an overuse syndrome usually does NOT cause pain in the early stages of the overuse. Carrying a backpack could certainly be considered to be an overuse syndrome; after all, it has the major characteristic of an overuse syndrome, which is a repetitive physical stress to the body to support the weight of the backpack. When the body is physically stressed by something like carrying a backpack, it often requires many years before the overuse results in a breakdown of the musculoskeletal (neuro-myo-fascio-skeletal) system. Think of any other physical overuse syndrome. It can takes years or decades before tennis elbow, carpal tunnel syndrome, or osteoarthritis of the knee pain develops. Not that there is always an even relationship between structural damage and pain and dysfunction, but at some point, there has to be an effect… Again, mechanics have to matter at some point. Even take something like smoking cigarettes. Could we do a study investigating whether smoking cigarettes is related to the presence of lung cancer or heart disease in adolescents? I am sure that if we do, we will find zero causality between smoking and adolescent heart disease or lung cancer. Would this prove that smoking is healthy for adolescents? No. It is just that the cumulative effects have not yet been experienced.