Does fascia or muscle hold memories?

Many manual therapists in their practice have experienced a phenomenon wherein when they touch on a particular area of the clients’ body during a therapeutic session, it provokes memories or traumatic events from the client’s life. This feeling is also accompanied by what is often described as an emotional release. Paolo Tozzi, an Italian osteopath, posed the following questions in an editorial in Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies:

Many manual therapists in their practice have experienced a phenomenon wherein when they touch on a particular area of the clients’ body during a therapeutic session, it provokes memories or traumatic events from the client’s life. This feeling is also accompanied by what is often described as an emotional release. Paolo Tozzi, an Italian osteopath, posed the following questions in an editorial in Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies:

- Can memories be held in the fascia?

- And are these memories accessible during manual therapy?

However, literature mentioned that memory is in the brain, not in the tissue or muscle. So Paolo proposed some possibilities:

- Neuro-fascial memory

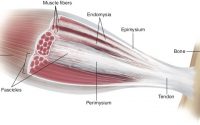

Research has found that fascia is richly innervated with nerve endings, making it a “tissue of communication.” Under certain dysfunctional conditions, a neuro-fascial interaction may be responsible for the setting of a local tissue “memory” (peripheral sensitization). Thus, touch or manual therapy may “unload” the tissue, causing a change in neural input to the brain which may trigger the memory.

- Fascial memory

Paolo argued that “memories” in the body may be also encoded into the structure of fascia itself. Collagen is deposited along the lines of tension imposed or expressed in connective tissues at both molecular and macroscopic level. Thus, mechanical forces, such as in postures, movements, and strains, can dictate the sites where collagen is deposited. Thus architecture changes due to habitual lines of tension, providing a possible “medium term memory.”

- Extracellular matrix and tissue memory

In addition, the elastin fibers and in various cells throughout the connective tissue, fibroblasts, mast cells, plasma cells, and fat cells, which are relatively durable and long-lasting, may represent “long-term memory” of the ground substance. It has been suggested that the cellular network of fibroblasts within loose connective tissue may support yet unknown body-wide cellular signalling systems.

- Muscle cells

Muscle memory refers to individuals with a history of previous training which can acquire force quickly on retraining. This is mostly attributed to motor learning in the central nervous system. However, a recent research study showed that “memory” is stored as DNA-containing nuclei, which proliferate when a muscle is exercised. In addition, those nuclei aren’t lost when muscles atrophy.

Paolo further postulated that during a manual therapy session: “the interaction of vibrational, biomagnetic, and bioelectric fields between therapist and client allow an exchange of information about the history and the present status of the living matrix. The information encoded in cell and tissue structure and activity may be read holographically, by tuning to the appropriate frequencies. This may even lead to a recall of past traumas and of an array of related sensations.”

It was suggested that manual therapy might affect various forms of memory, producing tissue changes from subatomic to global effects.

Tom Myers responded to Paolo’s article by saying that the choice of the word “memory” is unfortunate and misleading. The idea of “fascial memory” is similar to invoking “energy” another term used commonly among many manual therapists from osteopaths to Reiki masters to label a whole class of mysterious phenomena without truly understanding the actual mechanism.

Thus, Tom suggests re-framing the query: “Does fascia contribute to awareness?” We should focus on how these tissues contribute to the rich experience we call “awareness” or “consciousness.”

Awareness (and therefore memory), according to Tom, is a distributed phenomenon. All tissues participate, but they participate differently. The nervous system is our alarm clock. It registers difference over time, and as part of this, locates memories in time, and therefore our immediate temporal experience of memory is always neurological. Emotional memory, such as that invoked in deep bodywork, is always a fluid event, a change in the body’s fluid chemistry.