Exploring the Pain-Relieving Power of Exercise, Stretching, and Cold Therapy

Exercise, stretching, and cold therapy are known for their wide range of health benefits, from improving strength and flexibility to relieving pain. One of the most fascinating aspects of these activities is their ability to reduce the perception of pain—a phenomenon that has intrigued scientists for years. Research has shown that exercise, stretching, and cold water immersion (a form of cold therapy) can activate the body’s natural pain-relieving mechanisms, creating what scientists call hypoalgesia, or a decrease in pain sensitivity.

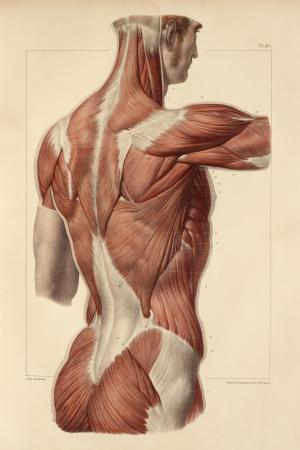

One type of pain reduction, known as Exercise-Induced Hypoalgesia (EIH), occurs when physical activity lessens pain perception through neural pathways. The effect is most noticeable in the exercised muscles but also spreads to other parts of the body. This broad effect suggests that both local (in the exercised muscles) and systemic (throughout the body) mechanisms are at play. Another pain relief process, Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM), operates through a “pain inhibits pain” principle. When one painful stimulus, such as immersing a hand in cold water, is introduced, it can actually lessen pain felt in another area of the body by engaging the brain’s descending pain pathways.

Given that both EIH and CPM involve reducing pain through natural inhibitory mechanisms, researchers are investigating whether stretching—a common exercise often involving some discomfort—may also work through similar pain-modulating pathways.

How Stretching Might Reduce Pain

Stretching, frequently prescribed in rehabilitation to increase flexibility and ease pain, has shown to reduce pain sensitivity in a manner similar to EIH and CPM. This pain-relieving effect, termed stretch-induced hypoalgesia, can be measured by an increase in the pressure pain threshold (PPT)—a measure of how much pressure can be tolerated before pain is felt. Researchers are still unclear on the precise mechanisms by which stretching reduces pain. However, it’s thought that the discomfort from stretching might stimulate CPM-like pathways, where the brain engages its own pain relief mechanisms in response to this mild discomfort.

Studies indicate that stretching may improve flexibility not by altering the muscle’s physical properties, but by increasing the individual’s tolerance to the stretching sensation itself. For instance, massage therapy and other techniques that prepare the muscles before stretching can increase range of motion, possibly by activating similar pain-modulating pathways. Repeated exposure to the stretch sensation, especially to the point of slight discomfort, can gradually enhance tolerance, likely making the stretch sensation more tolerable over time. This response hints at the idea that stretching engages natural pain modulation mechanisms, especially at higher intensities.

Cold Therapy, Exercise, and Pain Modulation: A Comparison

To explore the potential link between stretching and other pain-modulating techniques like cold therapy, researchers from School of Kinesiology and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Central Florida, compared changes in pain sensitivity across different interventions. Specifically, they examined the effects of a cold water immersion task, a moderate-intensity stretch, and a low-intensity stretch on the PPT. Cold water immersion, often used to measure CPM, involves placing a hand in cold water to induce a controlled level of pain, which can then be compared to pain reduction in other areas. This method has proven effective at stimulating the body’s pain-modulating responses.

The study found that cold water immersion resulted in a significantly greater increase in PPT compared to moderate-intensity stretching, suggesting a stronger hypoalgesic effect. These results imply that moderate-intensity stretching may not reach the threshold required to activate CPM-like pain modulation, whereas cold water immersion triggers a more robust response through natural pain-inhibiting pathways. Additionally, low-intensity stretching showed similar pain-reducing effects to cold therapy, highlighting that even a mild stimulus can reduce pain perception.

Pain Tolerance and Psychological Influences

Pain is a complex phenomenon influenced by not only physical factors but also psychological ones, such as anxiety and resilience. Research suggests that people’s psychological profiles—such as their level of pain-related anxiety or fear of pain—can influence their sensitivity to pain and their response to different pain-reducing interventions. For example, individuals with lower levels of pain-related anxiety may experience greater pain relief during cold water immersion compared to those with higher anxiety.

Interestingly, this link between psychological factors and pain relief appears more pronounced with cold therapy than with stretching. These findings suggest that personal characteristics like anxiety might influence pain relief more strongly when using painful or intense stimuli, such as cold water immersion. However, stretching, especially at low intensity, may provide pain relief without significant influence from psychological factors, making it potentially more suitable for individuals sensitive to pain or with high anxiety.

Implications for Rehabilitation and Pain Management

These findings have significant implications for designing effective pain management strategies, especially in rehabilitation. Knowing that cold therapy activates strong pain-modulating responses while stretching may provide gentler relief, therapists can tailor interventions based on a person’s pain sensitivity and psychological profile. For example, for those who might benefit from activating strong pain-inhibitory pathways, cold water immersion could be introduced alongside other rehabilitation techniques. Meanwhile, stretching remains a useful and accessible way to enhance flexibility and reduce discomfort in a way that is tolerable for a wide range of individuals.

Another insight is that the intensity of the stretch matters. Stretching at a higher intensity may be necessary to achieve the same pain-modulating effects as other, more intense stimuli, while still remaining gentle enough for routine use. This could help optimize stretching as a pain-relieving tool in both clinical settings and everyday routines.

Conclusion

The body’s ability to manage pain through natural inhibitory mechanisms is a powerful tool for enhancing quality of life, and activities like exercise, stretching, and cold therapy offer accessible, non-pharmacological ways to tap into this system. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia and conditioned pain modulation are two processes that work through the central nervous system’s pain-relieving pathways, and stretching may engage similar responses, especially when mild discomfort is involved. The comparison between cold water immersion and stretching shows that while cold therapy elicits a stronger response, stretching remains a versatile tool for pain relief that may be especially effective for those with lower pain tolerance or higher anxiety.

As research continues, understanding the relationship between physical and psychological factors and individual pain responses will help create more personalized and effective pain management strategies, supporting both physical rehabilitation and everyday well-being.