Joe Muscolino on the rediscovery of Interstitium

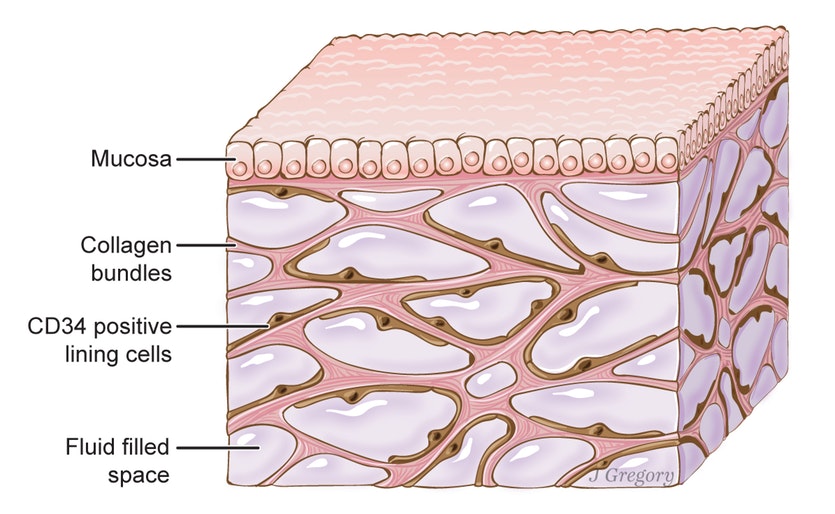

A new study by researchers from NYU School of Medicine reveals, what we already know, that there is a zone of tissue known as the interstitium that is composed of layers of interconnected, fluid-filled compartments, below the skin’s surface, which surrounds musculature, vessels, and nerves, and lines the digestive tract, lungs, and urinary system. The interstitium is composed of a meshwork of strong collagen and flexible elastin connective tissue protein fibers. As such, the interstitium may act like a shock absorber that keeps tissues from tearing as visceral organs, muscles, and vessels squeeze, contract, pump, and pulse.

Interstitium Already Well Recognized in the Manual Therapy World

“In sum, we describe the anatomy and histology of a previously unrecognized, though widespread, macroscopic, fluid-filled space within and between tissues, a novel expansion and specification of the concept of the human interstitium.”

While this “discovery” of this “previously unrecognized” interstitium from the medical world has recently attracted a lot of media hype and attention, it has already been very well recognized in the world of manual therapy.

- Gil Hedley demonstrated this quite a few years ago and called it the Fuzz; more recently he has termed it perifascia.

- Jean-Claude Guimberteau also has shown this network in his endoscopic study Strolling under the Skin, which he called the Multimicrovacuolar Collagenic Absorbing System, MVACS, a network of collagen fibrils forming microvacuoles that appeared to be randomly organized but can adapt itself to various stress forces.

- Deane Juhan’s book, Job’s Body similarly has described the qualities of the fascial connective system interstitium.

- And the Stecco Family out of Italy has researched and published numerous articles on the subcutaneous fascial interstitium.

- Then there is all the wonderful work of Robert Schleip, Thomas Findley, and so many others.

- And all manual therapists who perform skin-rolling techniques recognize the importance of the subcutaneous fascial interstitium.

- Indeed, any massage therapist who has been in practice for a few months/years or longer can easily feel and palpate changes in the fibrous fascial aspect of this “newly discovered” interstitium.

Comment by Joseph E. Muscolino:

It is ironic that this very article that is showing recognition of the soft tissues of the body, reveals its ignorance of any research that has already been published about that very soft tissue. By describing it as “previously unrecognized,” this demonstrates the long-standing bias against soft tissues by the Western World of Medicine. This is bittersweet. We manual and movement therapists should be happy and view as sweet that tissues that we long recognized as being important are finally beginning to be recognized as such. Yet it is a bitter pill to swallow that these researchers seemed to think that they just discovered something new that we have been researching, writing about, and working with, for decades!

Pardon my historical political analogy, but it reminds me of Cristoforo Colombo (his real name folks, Christopher Columbus is his “anglicised name” – even as most of us know his name shows a bias, doesn’t it?) “discovering” the “new world” when there were already tens of millions of people there who felt like this world had already been “discovered” by them thousands of years before and was not “new” to them at all!

Any manual / massage therapist who has some palpation experience, can feel the qualitative difference between the soft homogenous fluid-like texture of a baby or young person’s subcutaneous interstitium, and the more fibrous (“cheese-clothy”, “chicken wiry”) texture of the same interstitium as fibrous collagen is laid down within it as a response to strengthen and reinforce the tissue in response to the physical forces that are transmitted through the interstitium with use and aging. In effect, this qualitative change in interstitial tissue texture is caused by a quantitative change in the laying down of tough collagen fibrous tissue within the otherwise soft fluidy gel-like interstitium.

The Interstitium as an Organ?

The authors described this network interstitium as an organ in its own right, which has created a new excitement regarding fascia.

Although long-recognized by the world of manual therapy, the interstitium has usually been described as a tissue, not an organ. Whether the interstitium is defined as a tissue or organ depends on the definitions used for these two terms. A common definition of a tissue is: two or more different cells, their cellular products, and the contents located between them, all acting together for one function. Certainly the interstitium fulfils the requirements of that definition. Whereas, a commonly accepted definition of an organ is: two or more different tissues acting together for one function. Does the interstitium meet this definition? I am not sure that it does. It depends on how flexible and creative we are with the inclusion of various tissues within the interstitium. For example, are the vessels that run through the interstitium part of the interstitium? If so, then we definitely have multiple tissues within the interstitium. But aren’t these vessels really part of the circulatory system? Can they be part of both the circulatory system and the interstitium? And even if we answer this in the affirmative, vessels are actually organs, not tissues, because a vessel contains two or more different tissues acting together for one function. So that would mean that the interstitium is actually not even an organ, but rather an organ system… Before we drop down too far into the rabbit hole of anatomy geekdom, perhaps it is not so important how we define the interstitium, but rather that we recognize the tremendous functional importance that the interstitium has in human physiology.