Philosophy About the Usefulness of Myofascial Lines

By Steven Goldstein

Let’s chat about lines of myofascial tension

I have upcoming courses in June 2024 focusing on the shoulder, scapula and upper extremities, whose model is derived from Thomas Myers myofascial arm lines.

I’ve found, although not in contemporary fashion these days, an understanding of such, is still helpful in a clinical sense.

There is a tendency these days to reject the bio-mechanical model as old 20th century outmoded paradigm when viewing the relational and interface with fascia from an anatomist standpoint.

They’re many erudite discussions via social media threads, about being cautious of the language we use to describe what is occurring when we place our hands on a client and what we attribute to the causal effects that occur.

In fact, much of the discussion concerns biases regarding our own thought processes as to what we think is happening when feel a change in tone or tension. Since it is subjective, how do we really know?

As an older educator, I am not a fossil stuck with my head in the sand. I do embrace change as necessary so that I am not perpetuating myths. However, the current narrative regarding pain science, evidence-informed and evidenced-based science, has coloured a landscape that is now very confusing for many.

Especially in the education sector of manual and massage therapy. How do we unlearn what we’ve learned, and do we throw everything out as outmoded and perpetuation of myth?

As an older practitioner, steeped in the history of the profession, I’m chaste (restrained) to just say all of it is bullshit.

Thus, I am going to present what is considered outmoded by some, but, in my estimation, still clinically relevant, that is, lines of myofascial tension.

This at best is still a construct attempting to isolate components of a whole system interaction at multiple levels of complexity. It has been drawn from all manual therapy professions; physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic and manual therapy.

The usefulness has shown itself over time, and that is why I still persist. Not so much with the ‘why’, because that always seems to change, but the how and it resultant effect.

So here goes, once again.

Myofascial lines show the locomotor system and the myofascial tissues as being one unit that always functions as a whole.

They have evolved through our understanding of myofascial slings acting in concert.

Gary Carter in his excellent chapter of Linus Johansson and Martin Lundgren’s Movement Integration text, speaks of the evolution of this line of thought.

Carter states’ “We are living in a time where the ideas of anatomy have been challenged with new views of our structure, different considerations of biomechanics, the reviewing of how our structure generates its stability and what constitutes “posture,” whatever that may mean. We have had many visionaries create wonderful insights and new explorations of our anatomy and function which shift perspective, leading to creative and different ways of understanding manual therapies, training systems, movement practices, through to some medical procedures.”

“Kurt Tittel was a visionary and pioneer and along with Raymond Dart explored a series of sling-type arrangements in the body, which we find in his seminal work Muscle Slings in Sport, first published in 1956.

Tittel obtained his Doctorate of Medicine at the University of Leipzig and in 1952 he established a sports medicine practice.

He was interested in anatomy and, more specifically, the functional anatomy of the athlete. In 1964, he became director of the Independent Institute for Sports Medicine in Leipzig, continuing to become the president of the Society of Sports Medicine. With over 500 publications in the field of sports medicine, he is considered the father of sports medicine in Germany.

Tittel understood that muscle, bone, and tendon could not be fundamentally understood without considering their relationship to the whole individual.

Thomas Myers is a visionary, a practitioner of Rolfing and structural integration and was also an anatomy teacher to the Rolf Institute in the early 1990s. He developed a way of teaching myofascial anatomy in the method of a game, where he would connect up muscles along the front, back, sides, etc. of the body.

Myers noticed that all anatomy books suggested a “single muscle” theory and his teacher Ida Rolf was suggesting they are all connected through the fascia. He was also shown an article by Raymond Dart linking the muscles through the trunk as a double spiral arrangement.

Tom Myers’s response to this was “why stop there?” and he extended the double spiral arrangement into the legs to make it a whole body structure, becoming the world recognized Spiral Line from the Anatomy Trains.

Myers then continued creating those continuities into the many connected muscle and fascial lines from head to toe. From this notion, he produced his seminal work, Anatomy Trains, creating a connected whole body view of our myofascial body with a new way of seeing the muscle map as an interconnected network.

Lundgren, Martin; Johansson, Linus. Movement Integration Chapter 17 Gary Carter (pp. 142-145). North Atlantic Books. Kindle Edition.

Myofascial Lines of Tension: Arm Lines

I was so fascinated by the relational aspects of the Arm Lines when Thomas Myers presented this back in 2001. Nearing a quarter century, how useful are these for us in the clinical setting?

In his preamble in the excellent book Fascia in the Osteopathic Field (2017) by Liem, Tozzi and Chila; Myers writes on Myofascial Meridians in Practice Chapter 31.

Myers waxes lyrical about osteopathic influences and his professional interest as it matured. He did train with Ida Rolf in 1978.

Settling upon what he referred to as ‘spatial medicine’. That is; “what programme of activities, exercises, or forms of attention would allow our clients (and more importantly the next generation) to avoid widespread pain and pathologies that result from poor body use. (Alexander 1932).”

How do proper movement and sustainable posture develop and mature (Bainbridge-Cohen 1993)?

Where does the natural go wrong (Bateson 1979)?

Or are we outliving our joint design (Alexander 1992)?

How much body pain is simply ‘mismatch’ between our ‘paleolithic environment’ in which our species developed versus the self-created urban environment in which most of lives (Lieberman 2013)?”

What is the minimum curriculum of movements required to develop and maintain decent biomechanics?

Very interesting questions.

Spatial Medicine, according to Myers, is the study of how our body develops in space, moves through and manipulates the environment, and deals with the inner and outer spatial relationships.

Myers states, “it is imperative of our era that we articulate a new biomechanics that applies consistently from the molecular level to the organismic.”

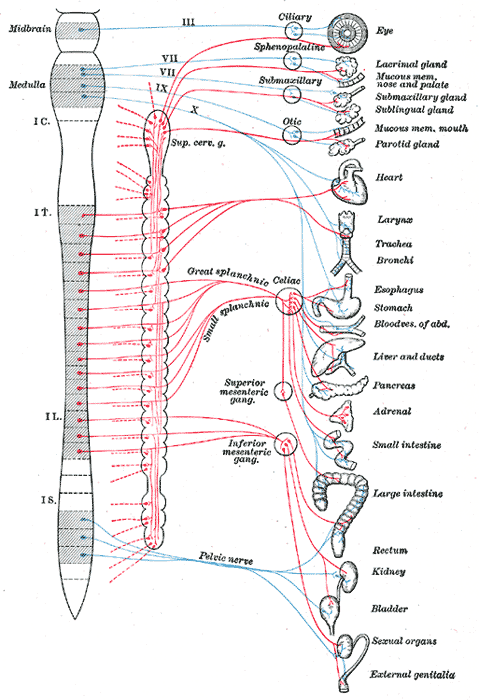

Our lens is to look at a particular myofascial line orientation, that includes as a unitary net enveloping 600 skeletal muscles with 12 myofascial meridians.

The arm lines are considered from Myers standpoint, ‘helical lines’, that is, running more obliquely and thus crossing the body’s midline.

The helical lines create, coordinate, and limit rotational movement in the horizontal plane, as well as more common oblique movements that spiral across various planes and maintain postural rotations in the body.

The arm lines – since helical lines augment the force of the arms by extending their lever arm across the trunk to the legs. The arms themselves have four distinct, connected lines designed to facilitate the wide mobility of the upper appendage.

SBAL Superficial Back Arm Line – runs from the occiput and thoracic spinous processes out over the shoulder and down over the elbow to the extensor group on the back of the wrist and fingers. The SBAL could be considered the top side of a bird wing.

SFAL Superficial Front Arm Line – runs from the trunk – ribs, sternum, hip and spine – out and down the inner and underside of the forearm with the carpal flexors and the longer tendons through the carpal tunnel to the palmar fascia and digits. The SFAL corresponds to the underside of a birds’ wing and is the primary source of power we impart to balls, axes, caresses and manual therapy.

DBAL Deep Back Arm Line – runs deep to the SBAL, including rhomboids, the rotator cuff, the triceps and the fascia down to the little finger side of the hand. The scapula is a tethered ‘sesamoid’ bone within this line. The DBAL corresponds to the trailing edge of the bird’s wing, and its misuse in the human arm is very common, leading to many shoulder stability dysfunctions.

DFAL Deep Front Arm Line – runs from the ribs via the pectoralis minor and clavipectoral fascia to the biceps and down the inner arm to the thumb. The DFAL corresponds with the bird wing, and similarly controls the arm’s angle. Through the thumb it is connected to our grip and stability. Its’ misuse is common a factor in many ‘hunched’ upper body postural compensations.

Fascia in the Osteopathic Field (2017) by Liem, Tozzi and Chila; Thomas Myers: Myofascial Meridians in Practice – Chapter 31 pp.317-325.

Within the context of Fascial Therapy, we view the lines clinically as an organised ‘linkage’.

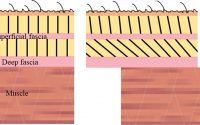

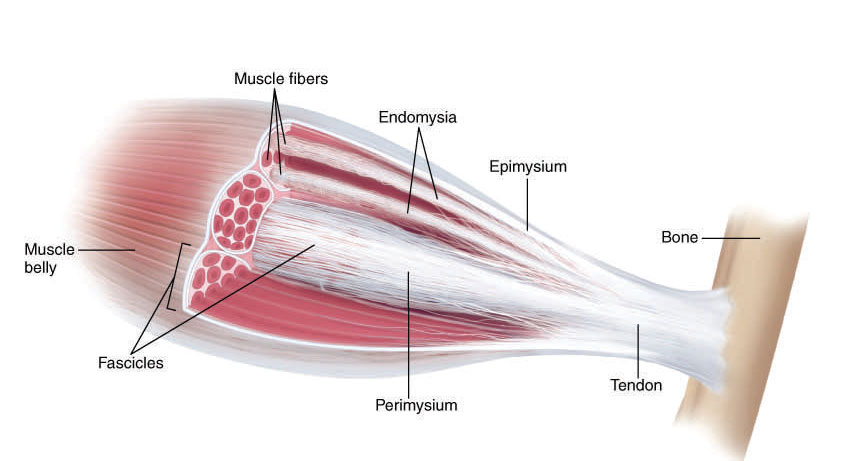

Each component, whether joint, muscle, tendon, ligament and nerve, visceral, vascular; all are encased within the connective tissue matrix that is in relational connection.

If we take an axiom from Gary Ward, ‘joints act, muscles react’; this premise is why I’ve integrated so much joint application to the fascial content I instruct.

For example, the facet joints of the spine, to which the arm lines are tethered through spinous process attachment, when fixated as they invariably are in the thoracic region, will create tension throughout the line, which often is assessed as muscle tightness or restricted elbow extension.

Once the thoracic segment is slightly articulated utilising either low load MET or PRT functional technique or a combination of both, the space created affects the tonal quality of the entire upper limb, i.e. muscles appear to soften, and lo and behold, you have increased range in that plane of elbow movement.

Thus, carpal tunnel dysfunctions should, in my estimation, be viewed through a macro lens, taking in the spine, pelvis, shoulder and arm lines to reduce any compensatory participants in the wrist dysfunction.

And vice versa. The radial carpal joint can affect rotator cuff tension. Once this understanding is reached, how you treat these conditions change.

Understanding the relational components of a line allows one to understand relationships that exist between all soft-tissue components.

Its’ not that you’ll have success 100% of the time, but you use your time more efficiently and with greater positive clinical outcomes.

This type of assessment is what I term ‘benchmarking’, allowing us to contrast and compare motion and surface tissue restrictions.

And decide if we should be working separately or in tandem, both superficial and deep, addressing capsular, ligament or treating superficial myofascial ‘sleeve’ restrictions, if I may use that terminology.

Treating from a multi-dimensional perspective is a hallmark of Fascial Therapy training.

Within this approach, most of the time, muscle is the last to be treated, unless you deem it to be the primary causal mechanism for lack of range of motion, hypertonic or trigger point.

As some of my esteemed colleagues wish you to remember, eccentric loading and concentric loading still palpates as a tight muscle.

Understanding why a muscle is supposedly ‘locked long’ versus ‘locked short’, requires you to have a dive into research concerning differing roles how concentric versus eccentric loading muscles function in training and sport. Or come from an applied kinesiology perspective that is controversial from an evidence based perspective. Can’t help with bring some woo-woo.

When I assess a lack of scapular retraction, for instance, instead of attempting to utilise a compressive force on the muscle tissue, I will attempt to restore a greater range of motion.

With modified MET, we always place into the ‘ease’ direction and have the client exert low force effort in the direction of ‘bind’.

This ensures we work within tolerances of pain and discomfort and avoid over recruitment, instead affecting joint receptors and intrinsic mono articular musculature. Ask for 5% percent patient effort in the direction of restriction for 3-10 seconds, on release mobilise multiple directions. Change usually occurs and motion is restored.

If you are interested in joining me on one or several of my courses https://terrarosa.com.au/product/hands-on-workshops/polyvagal-theory-with-steve-goldstein/spine-scapula-thorax-masterclass/