The neuromyofascial system, a whole-body organ of communication

Fascia in Motion by Elizabeth Larkam is a comprehensive guide to fascia-focused Pilates movement, represents a lifetime of Larkam’s work, complete with color photographs and tables documenting the requirements, intent, attributes and outcome of hundreds of movements in exquisite detail.

The following article is an excerpt of Fascia in Motion (copyright Handspring Publishing)

In Latin, fascia means “bundle, bandage, strap, unification, and binding together” (Oschman, 2016). “Fascia is the tensional, continuous fibrillar network within the body, extending from the surface of the skin to the nucleus of the cell. This global network is mobile, adaptable, fractal, and irregular; it constitutes the basic structural architecture of the human body” (Guimberteau & Armstrong, 2015).

Physical force, provided by gravity and physical movement, is a primary regulator of life’s form and function. In older individuals, somatic dysfunction and postural disorders are common, which modify transmission of forces through the tissues. Unbalanced tissue tensions can affect mechanotransduction. Other factors, in addition to age, that influence degradation of the fascia include exposure to ultraviolet light, mechanical wear and tear and inflammation, which decrease the volume, number and quality of the tissue fibers. Normally, the extracellular matrix is under tension, which stimulates mechanochemical transduction. The degree of stiffness of human fibroblasts decreases and this may influence the cell’s response to mechanical stimulations.

Fibrils become gradually less resistant to tension. Intrafibrillar tension decreases and fibrils lose their dynamic capacity to return to form. Reabsorption of fluids is less efficient and diminished vascular profusion decreases nutritional supply. Pro-inflammatory physiology underlies the development of age-related diseases – inflammation promotes pathologic tissue damage and activation of fibroblasts which play an active role in the persistence of chronic inflammatory reactions. Dysfunctional connective tissue, caused by mechanical stresses or inflammation, alters a number of factors including myofascial relationships, muscle balance, proprioception, and vascular and lymphatic drainage.

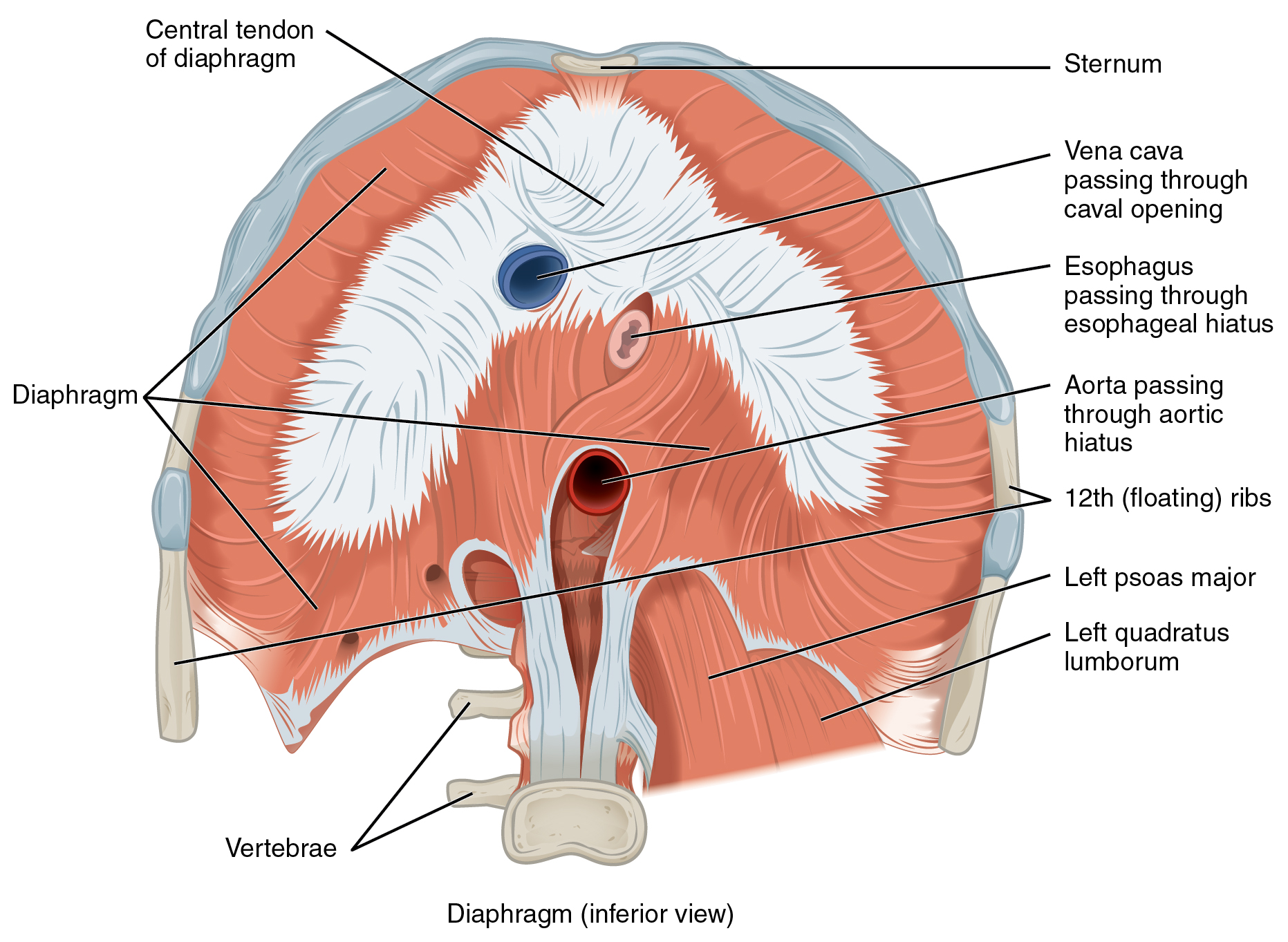

Fascia is the soft tissue component of the connective tissue system that permeates the human body; it interpenetrates and surrounds muscles, bones, organs, nerves, blood vessels and other structures. Fascia is an uninterrupted, three-dimensional web of tissue that extends from head to toe, from front to back, from interior to exterior. It is responsible for maintaining structural integrity, and for providing support and protection; it also acts as a shock absorber. Fascia has an essential role in blood glow and biochemical processes and provides the matrix that allows for intercellular communication. Fascia functions as the body’s first line of defense against pathogenic agents and infections after injury, it is the fascia that creates an environment for tissue repair. (Paoletti, 2006, cited in Oschman, 2016)

Publications influencing fascia-focused movement criteria

The practice of training fascia in Pilates has been inspired by Anatomy Trains: myofascial meridians for manual & movement therapists by Thomas W. Myers. The first edition was published in 2001. Pilates teachers seeking to augment their movement education with interdisciplinary study applied the seven categories of myofascial meridians described by Myers to the Pilates mat and apparatus repertoire and began the paradigm shift from “isolated muscle theory” to the “longitudinal anatomy”.

Systematic review of the Anatomy Trains® myofascial chain system

Many therapists and movement educators who address fascia orient themselves to concepts of myofascial chains. The assumption is made that the muscles of the human body do not function as independent units. Instead, they are regarded as part of a tensegrity-like, body-wide network, with fascial structures acting as linking components. Since fascia can transmit tension and has proprioceptive and nociceptive functions, myofascial meridians could be responsible for disorders and pain radiating to remote anatomical structures. Myers defined seven categories of myofascial meridians connecting distal parts of the body by means of muscle and fascial tissues. The system of myofascial meridians represents a promising approach to convert tensegrity principles into practice.

The central rule for the selection of a meridian’s components is a direct linear connection between two muscles. Myofascial meridians are based on anecdotal evidence from practice and have never been verified: although widely used in exercise therapy and osteopathy, the scientific basis for the proposed connections is still a matter of debate. The systematic review article, “What is evidence-based about myofascial chains: a systematic review” by Wilke et al. (2016) aimed to provide evidence for six of the myofascial meridians based on cadaveric dissection studies. Extensive structural continuity was clearly verified for the Superficial Back, Back Functional, and Front Functional Lines. There was moderate evidence for the Spiral and Lateral Lines and poor evidence for the Superficial Front Line. This review raised doubts about the existence of a Superficial Front Line: there is no structural connection between the rectus femoris and rectus abdominis muscles. The review suggested that most skeletal muscles of the human body are directly linked by connective tissue. 62 articles suggest strong evidence for the existence of three myofascial meridians: the Superficial Back Line (all three transitions verified), the Back Functional Line (all three transitions verified), and the Front Functional Line (both transitions verified). Moderate-to-strong evidence is available for parts of the Spiral Line (five of nine verified transitions) and the Lateral Line (two of five verified transitions). No evidence exists for the Superficial Front Line (Wilke et al., 2016).

This article is an excerpt of Fascia in Motion (copyright Handspring publishing, used with permission)