The role of intramuscular tendon in strenuous hamstring and quadriceps muscle strains

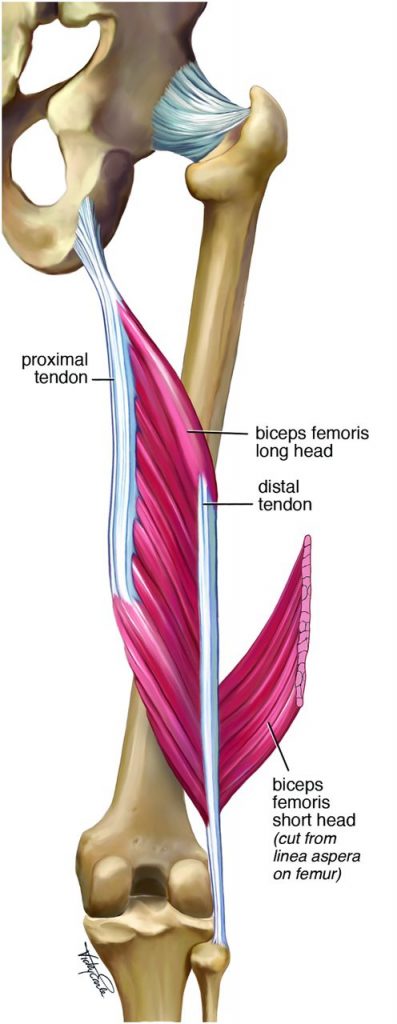

In contact sports such as rugby, some hamstring and quadriceps strains have been reported to take much longer to repair than others. Peter Brukner, a sports physician from Australia, reported that thigh muscles, including biceps femoris and rectus femoris, have significant intramuscular tendons. The attached intramuscular tendon extends for a significant distance from the bony attachment into the muscle belly. Because the pathology of most muscle injures occurs at a musculotendinous junction, when the athlete reports pain within a muscle belly, it may indicate injury of the intramuscular tendon.

Figure: (A) MRI showing myofibril tearing (solid arrow) on either side of the intramuscular tendon rachis of the rectus femoris to create a feather-like appearance. From Brukner and Connell 2016, Creative Common)

The intramuscular tendon structurally is different from the usual “free” tendon, which can be found at both ends of the muscle leading to its bony attachment. Peter Bruckner and authors from Australia in another article proposed the term ‘Intramuscular aponeurosis’ or ‘intramuscular connective tissue’ to highlight the unique structural, behavioural, and pathologic properties.

The intramuscular tendon can have a variable appearance and vary between individuals, but are found as condensations of connective tissue within the lower limb muscles, most often biceps femoris and rectus femoris in the thigh, and gastrocnemius and soleus in the (lower) leg. Intramuscular tendons act as central supporting struts to which the muscle fibers attach. It is believed that they smooth and amalgamate asynchronous motor unit contribution.

Comparison of Intramuscular Tendon and Free Tendon

Structurally, the cross-sectional area of the isolated intramuscular tendon is substantially smaller than the free tendon it contributes to. Functionally, the free tendon can tolerate high tension (pulling/stretching) rates to store and release energy. In contrast, the intramuscular tendon is considerably stiffer and cannot store and release energy like free tendon.

Pathologically, the free tendon is prone to overuse pathology, becoming degenerative with little capacity to repair because there is little or no bleeding. Over time, the collateral regions of the tendon appear to remodel and increase tendon diameter to share the load and effectively strengthen the tendon. Thus, free tendons rarely rupture.

In contrast, intramuscular tendons have higher vascular perfusion than free tendon. Therefore, intramuscular tendon ruptures result in bleeding and inflammation, proliferation and maturation response, resulting in formation of hypertrophic intramuscular tendon scar tissue.

Intramuscular Tendon Injury

A muscle strain may tear the myofibrillar attachments from the intramuscular tendon, with resultant bleeding and edema. Occasionally, the damage may also involve a partial or complete tear of the intramuscular tendon. When the intramuscular tendon is damaged, the injury is regarded as a severe strain and has been found to cause a prolonged return to play. The author’s clinical experience showed that injuries involving significant intramuscular tendon injury require prolonged rehabilitation time and may be more prone to recurrence. Therefore, it is important that they are recognized early, especially in the elite athlete.

Intramuscular Tendon Injury Assessment and Medical Treatment

Injuries involving the intramuscular tendon can best be identified on MRI. At present, optimal management of these injuries that involve a significant tear of the intramuscular tendon involves surgical repair.

Application to Manual Therapy

Understanding that intramuscular tendons exist within a muscle belly can have implications for manual therapy, including massage and stretching. Given the tendency of fibrous scar tissue to accumulate in and around an intramuscular tendon injury, treatment techniques should be directed toward those that help to minimize scar tissue accumulation (once integrity of the tissue has returned). For example, cross-fiber techniques might be preferred over longitudinal strokes. As with any myofascial tissue tension, the exact joint angle used for stretching should be creatively worked with until the tension of the stretching force is experienced by the client at the location of the intramuscular tendon tear.