Throwing and Elastic Storage

Throwing and Elastic Storage By James Earls

Figure 1. A baseball pitcher. Photo By Antonio Vernon (original photograph) and Jjron (photoediting), at en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Recently, an article on biomechanics and evolution published in Nature (Roach et al., 2013) managed to attract much attention in the US-based press. It did so by comparing the throwing abilities of Homo Sapiens to that of our primate cousins. Headlines screamed ‘Scientists Unlock Mystery in Evolution of Pitchers’ which is, of course, an area of huge interest to the average American sports fan but also, as a therapist, piqued mine.

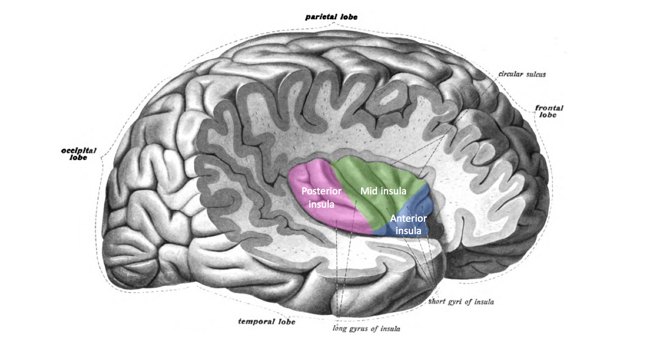

Within the Nature article, researchers compare many unique features that differentiate our shoulders from those of the apes, especially the lower torsion through the humerus that allows us a greater range of motion into external glenohumeral rotation. This increased range, according to the authors, allows more build up of elastic energy that can compensate for our weaker muscles. What they did not identify was which tissues are involved in this elastic mechanism.

An interesting addition within the article noted Darwin’s idea of how bipedalism has ‘emancipated’ the arms, allowing us the freedom to manipulate and to throw. It is my contention, however, that whilst lumbar extension allows us bipedalism it also provides us the ability to couple and as well as uncouple the arms from the rest of the body.

The longer waist that developed from Australopithecus (3.4 -1.9 million years ago) onwards also ‘decoupled’ the torso and the pelvis allowing a greater range of movement between the lower and upper limbs. By going to greater ranges of rotation and extension the pitcher/hunter/thrower can build up more elastic tension between each segment giving added acceleration to the distal hand. We can see this as a series of separate blocks and units (lower limb, pelvis, thorax, and upper limb) with the relevant elastic tissues between each) with the relevant elastic tissues between each however, this is only part of the truth within the body.

Following the demonstration of strain distribution by Franklyn-Miller et al. (2009), we can also view the relationships through a myofascial lens that emphasizes the fascial connections from one segment to another. In looking at the extreme cocking position of the pitcher in figure 1 we see the left hip and spinal extension along with the pelvic, thoracic and shoulder girdle rotation. These combine to increase the range of movement between the left hand and both feet that require a lengthening of the tissues in between. The lines of tension used for this extreme throwing position are somewhat predictable if we consider the myofascial continuities mapped out by Myers (2013, Figs 1 and 2).

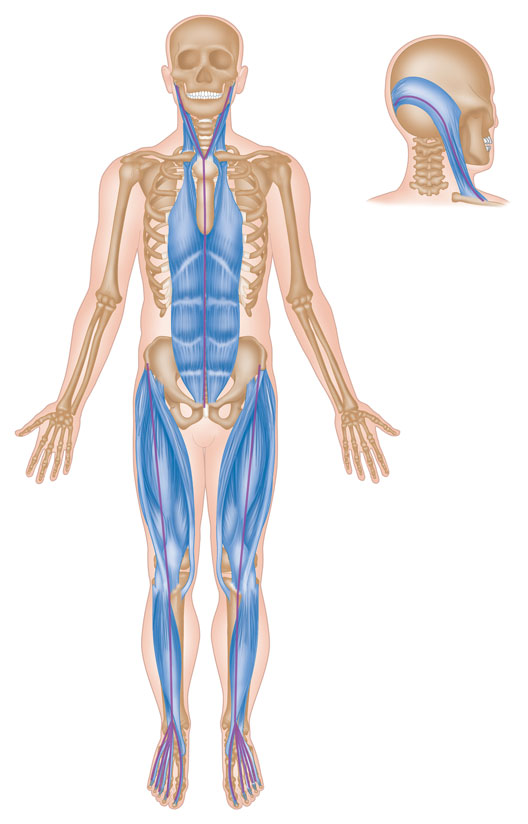

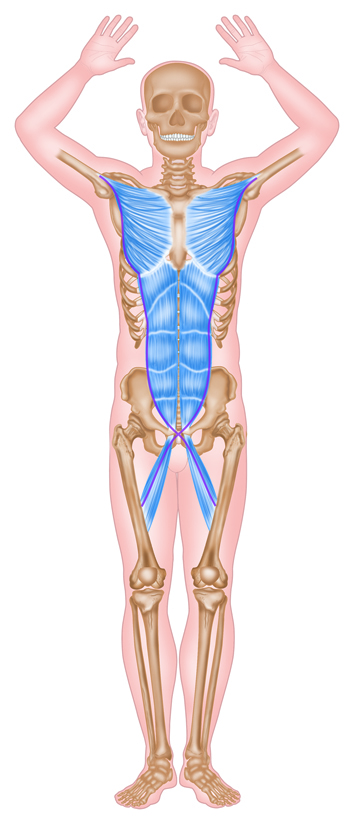

Left, Fig 2. The Superficial Front Line according to Myers (2013). Right, Fig 3. The Front Functional Line according to Myers (2013). Pictures Copyright of James Earls.

The pitcher’s left ‘Superficial Front Line’ (Fig. 2) is lengthened and thereby, one has to presume, elastically loaded. Much of the anterior thigh tissue from his left lower limb will assist with deceleration in the cocking phase, capturing kinetic energy in the elastic tissues that can then be released to assist the acceleration of the pelvis during the throw. However, this dynamic will not be limited to individual segments through in-series tensioning the anterior thigh tissues may also assist the rectus abdominis and sternal fascia in their role of spinal control.

Similarly, the adductors of the planted right lower limb assist with the control of the rectus abdominis and obliques with their connection into the pectoralis major via the so-called ‘Front Functional Line’ (Fig.3).

These in-series myofascial connections rely on appropriate ranges of motion through the whole system. If we are to recruit the potential energy created in the lengthening of the lower limb and trunk tissues to assist the recoil of the throwing arm we must be able to achieve complex positions similar to that shown in Figure 1. Without the extension and abduction of the left hip, the flexion, abduction and lateral rotation of the right hip (all of which require the extension and rotation of the spine) we could not pre-tense and elastically load the thigh and trunk.

Limitations in joints or tissues beyond the shoulder complex may therefore, contribute to overworking the local soft-tissue of the shoulder complex. The rotator cuff and pectoralis major, for example, will work harder to decelerate the cocking and to accelerate the throw. Any decrease of in-series tensioning will require more work from those tissues due to the loss of elasticity and distal contributions.

Through in-series tensioning the tissues of the lower body thereby assist the shoulder in its recoil (in parallel mechanisms will also be present but are beyond the scope of this article). By being able to see the line of force involved in long chain movement we can analyse the actions which should be present at each joint along the line and then investigate the reason for any restriction – motor control, soft tissue or joint limitations distal to a pathology could be responsible, or at least

contributory to the problem

Differential diagnosis and treatment programs can therefore be developed to address the issues distal to the affected site and that process can be aided with an understanding of the myofascial continuities.

Finally, returning to Darwin’s comment on the emancipation of the arms we can hopefully now see that lumbar extension provides us with both a freedom from weight bearing and access to manipulation. And, through the myofascial tethering, it also allows us a connection to the lower limbs, a greater range of movement that gives us the ability to harness more power though the system of our body. To utilize that power however, the pathways along the body must be clear – a truth not only for pitchers but for anyone using long chain complex movements.

References

Earls, J., Born to Walk: Myofascial Efficiency and the Body in Movement. Chicester; Lotus Publishing; 2014

Franklyn-Miller, A., E Falvey, R.. Clark, A. Bryant, P. Brukner, P. Berker, C. Briggs, P. McCrory. 2009. “The Strain Patterns of the Deep Fascia of the Lower Limb.” Fascia Research II. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier.

Fukashiro, Senshi, Hay, Dean C. and Nagano, Akinori. Biomechanical Behavior of Muscle-Tendon Complex During Dynamic Human Movements. Journal of Applied Biomechanics: 22; 2006; 131-147

Fukunaga, Tetsuo, Kawakami, Yasuo, Kubo, Keitaro and Kanehisa, Hiroaki. Muscle and tendon interaction during human movements. Exercise Sport Science Review: 30; 3; 2002; 106–110

Gorman, J. Scientists Unlock Mystery in Evolution of Pitchers. The New York Times 26 June 2013, Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/27/science/evolution-on-the-mound-why-humans-throw-so-well.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Gracovetsky, S. The Spinal Engine. Montréal; Serge Gracovetsky, PhD; 2008

Myers, T. W., Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists. Edinburgh; Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2013

Roach, N. T., Venkadesan, M., Rainbow, M. J., & Lieberman, D. E. Elastic energy storage in the shoulder and the evolution of high-speed throwing in Homo. Nature, 498(7455); 2013; 483-486.

James Earls is a writer, lecturer and bodyworker specialising in Myofascial Release and Structural Integration. Increasing the understanding and practice of manual therapy has been a passion of James’ since he first started practicing bodywork over 20 years ago. Throughout his career James has travelled widely to learn from the best educators in his field, including Thomas Myers, developer of the Anatomy Trains concept. James and Tom founded Kinesis UK, which co-ordinates Anatomy Trains and Kinesis Myofascial Integration training throughout Europe, and together they authored ‘Fascial Release for Structural Balance,’ the definitive guide to the assessment and manipulation of fascial patterns. He also authored Born to Walk, which presents the therapist with a powerful tool to assess and analyse movement.

Text & Figures Copyright of James Earls.