Tissue Flossing

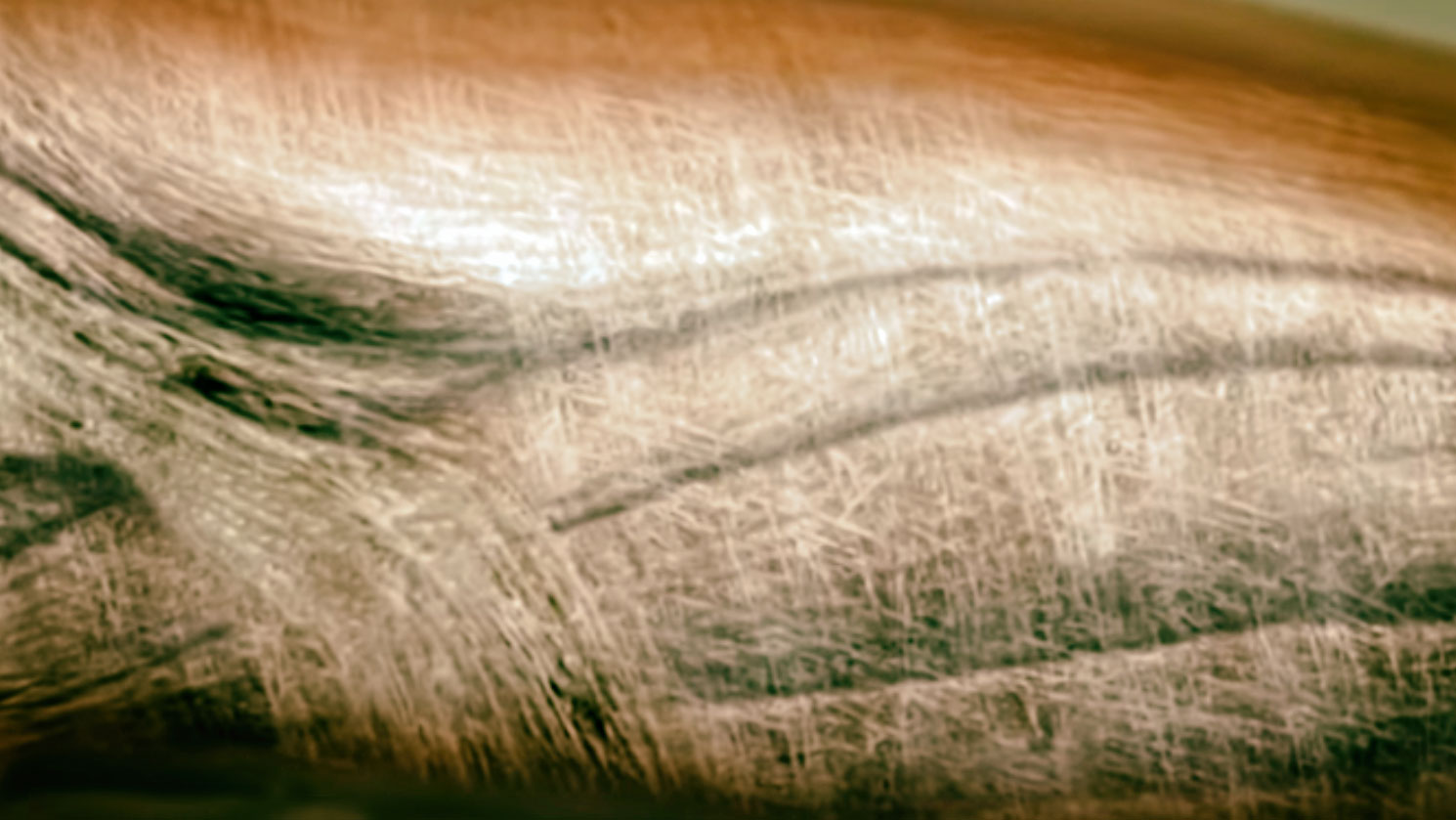

Tissue flossing, a myofascial intervention introduced in 2013 by Starrett and Cordoza, involves wrapping a latex band around a specific body area to enhance myofascial mobility, joint range of motion, athletic performance, and to reduce pain. It’s also used for blood flow restriction training. The application involves a specific technique where the band is overlapped 50% around the region, stretched to 50-90% of its maximum length, followed by active and passive movements during the treatment session lasting up to eight minutes.

Scott W. Cheatham and Rusty Baker wrote a guidleine for its use in the April 2024 issue of Clinical Commentary/Current Concept Review.

They define:

“tissue flossing is an intervention that uses a compressive latex band wrapped around a body region at a specific stretch length, followed by movement of the body region to manipulate the skin, myofascia, muscles, tendons, and/or joint structures.”

Despite its growing popularity in sports medicine, there’s a notable lack of consensus and formal guidelines on the proper use of tissue flossing. Given the absence of these guidelines and the variety of bands available with differing properties, physiotherapists discussed best practices for tissue flossing.

The current literature on tissue flossing, though not comprehensive or universally agreed upon, suggests that the technique can improve joint range of motion (ROM), muscle strength, athletic performance, and balance in certain cases, and may also reduce musculoskeletal pain. However, there is no established consensus on the optimal parameters for the intervention, such as the amount of band stretch, the wrapping pattern, or the total duration of the intervention.

Range of Motion

Research has documented that tissue flossing can result in short-term improvements in joint range of motion (ROM), muscle length, and tissue stiffness in both healthy adults and recreational athletes. Specific findings include:

- Joint ROM: Enhancements in active and passive ROM have been observed in the knee, ankle, and shoulder joints. Techniques like passive knee extension and straight leg raises have shown increases in muscle length, particularly for the quadriceps and hamstrings.

- Ankle and Foot: Improvements in active ROM for dorsiflexion and plantar flexion and better performance in weightbearing lunge tests among athletes.

- Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip Complex: Increases in hip flexion ROM have been reported using straight leg raise tests, though one study noted no significant changes using the modified Thomas test for hip and knee ROM.

- Upper Extremity: In amateur and recreational athletes, short-term post-intervention changes in shoulder passive ROM were noted, with significant perceived improvements despite nonsignificant physical changes. This perceived improvement may encourage ongoing treatment adherence.

- Tissue Stiffness: Ultrasonography and tensiomyography studies showed reduced stiffness in plantar flexors, hamstrings, and quadriceps post-intervention.

Intervention methods included wrapping either joints or soft tissue and incorporating both active movements (e.g., squats, lunges) and passive stretches (e.g., Child’s Pose) over sessions lasting between 2 to 8 minutes. Studies used a variety of controls for comparison, such as no intervention, different stretch intensities, and alternative therapies like self-myofascial rolling and kinesiology tape. The band stretch pressure was either preset or varied, with some studies quantifying this using sub-band digital pressure sensors.

Muscle strength, power, and athletic performance

Research on tissue flossing has documented positive short-term changes in muscle strength, power, and athletic performance following interventions:

- Muscle Strength and Power:

- Lower Extremity: Studies have shown improvements in ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion strength and power, measured using isokinetic dynamometry among healthy adults and athletes. Additionally, changes in knee flexion and extension strength were noted, although some studies reported nonsignificant changes for knee strength.

- Upper Extremity: Improvements in shoulder isokinetic strength (internal and external rotation) and power have been observed among both amateur and recreational athletes.

- Athletic Performance:

- Jump Performance: Enhancements in counter movement jump performance were recorded for the ankle and knee using force plates or mats, particularly among recreational athletes and professional rugby players.

- Sprint Performance: Positive changes in sprint performance following ankle tissue flossing were documented using digital speed timing systems.

- Balance and Landing: Post intervention improvements were noted in static and dynamic balance, hop distance, and jump landing performance, although some studies found nonsignificant changes in counter movement jump performance.

Treatments involved wrapping the joint or soft tissue of areas like the knee, ankle, thigh, and calf. Active movements were incorporated into sessions lasting 2 to 8 minutes.

DOMS

Research on the effects of tissue flossing on delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) following strenuous exercise has yielded mixed results. In one study, a tissue flossing intervention on the upper extremities led to a decrease in DOMS up to 48 hours post-exercise, as measured by a 100-mm Visual Analog Scale (VAS). Conversely, another study focusing on the lower extremities found no significant changes in DOMS, with pain measured using a 0-10 numeric pain rating scale.

The potential physiological mechanisms suggested include reduced inflammation associated with muscle microdamage and lowered intracellular osmotic pressure, which might decrease the sensitivity of nociceptors involved in pain perception.

Both studies involved wrapping soft tissue areas such as the upper arm and thigh, incorporating active movements for a total treatment time ranging from 2 to 6 minutes, using a recommended band stretch of 50% of maximal length without methods to measure or monitor band stretch pressure. Control groups in these studies did not receive any treatment.

Case Studies on Specific Conditions:

- Achilles Tendinopathy: A combined intervention of tissue flossing and self-myofascial release showed positive results in pain reduction and functional improvement.

- Keinbock’s Disease: Case reports on adult athletes indicated favorable outcomes using tissue flossing as the primary treatment.

- Osgood-Schlatter’s Disease: Similarly, adolescents and adult athletes showed improvement through tissue flossing interventions.

Clinical Studies on Pain Reduction: Elbow and Knee Pain: Post intervention improvements were noted in elbow and knee pain.

Interventions typically lasted 2 to 6 minutes and involved wrapping either joints (e.g., wrist, elbow) or soft tissues (e.g., upper arm, upper thigh), with active movements included. All studies adhered to a recommended band stretch length of 50% of maximal length without specific methods for measuring or monitoring band stretch pressure. Clinical studies often did not include controlled comparison groups, limiting the robustness of the findings.

Mechanism

Researchers have proposed various physiological mechanisms for the effects observed with tissue flossing. For joint ROM and tissue stiffness, it’s hypothesized that flossing might increase muscle stretch tolerance and improve myofascial properties. For muscle and athletic performance, enhancements in hormonal responses, reflex facilitation, and neuromuscular function are suggested, potentially influenced by vascular occlusion from the band’s pressure or the response upon its release. Ischemic preconditioning from flossing might also enhance athletic resilience to ischemia. For DOMS, the reduction in inflammation, intracellular pressure, and nociceptor sensitivity could be key. The effectiveness of flossing for specific injuries remains unclear due to multifactorial recovery mechanisms. Preliminary studies suggest that tissue flossing could produce similar effects to other myofascial interventions like IASTM and self-myofascial rolling, impacting various physical functions. These theories are not yet fully validated and require further investigation, especially to understand how tissue flossing works physiologically for different conditions and patient needs.

Precautions for Tissue Flossing:

When considering tissue flossing, several precautions need to be taken into account due to potential risks:

- Latex Allergy: Risk of allergic reactions.

- Circulatory Issues: Cyanotic skin or inhibited arterial and vascular function during treatment.

- Abnormal Sensations: Numbness or other unusual sensations during treatment.

- Patient Sensitivity: Intolerance, hypersensitivity, or high pain sensation, especially in injured areas.

- Skin Conditions: Fragile, sensitive skin, varicose veins, burn scars, or areas with body art.

- Connective Tissue Disorders: Including conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.

- Blood-Related Concerns: Use of blood-thinning medications or conditions that alter blood properties or sensations.

- Inflammatory and Swelling Issues: Acute inflammatory conditions, lymphedema, tissue edema, or swelling.

- Major Health Conditions: Cancer, pregnancy, hypertension, osteoporosis, unhealed fractures, diabetes, neuropathy, polyneuropathy, congestive heart disease, circulatory disorders, kidney dysfunction.

- Medical Devices: Presence of pacemakers, insulin pumps, and direct pressure should be avoided around these devices.

- Post Medical Treatment: Areas recently treated with injections, like steroids.

- Other: Insect bites of unexplained origin or direct pressure over critical areas such as face, eyes, arteries, veins, or nerves.

Contraindications for Tissue Flossing:

Tissue flossing should be avoided in certain conditions due to the risks of exacerbating symptoms or causing harm:

- Allergic Reactions: Presence of a latex allergy.

- Circulatory Issues: Arterial and vascular inhibited function, peripheral vascular disease, thrombophlebitis.

- Skin and Tissue Integrity: Fragile or sensitive skin, skin rash, open wounds, blisters, local tissue inflammation, burn scars, tumors.

- Connective Tissue Disorders: Conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or Marfan’s syndrome.

- Acute Conditions: Acute injury, infection, fever, contagious condition, acute inflammatory conditions, unhealed or unstable bone fractures.

- Major Health Conditions: Cancer, advanced osteoporosis, severe cardiac, liver, or kidney disease, lymphedema, tissue edema, or swelling.

- Blood-Related Concerns: Use of blood-thinning medications, bleeding disorders like hemophilia.

- Neurologic and Autoimmune Disorders: Neuropathy, polyneuropathy, neurologic conditions with altered sensation (e.g., Multiple Sclerosis), autoimmune disorders, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, complex regional pain syndrome.

- Other Medical Considerations: Uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, myositis ossificans, osteomyelitis, recent surgery or unhealed surgical sites.

- Medical Devices: Presence of pacemakers or insulin pumps (avoid treatment around these devices).

- Direct Pressure Sensitivities: Direct pressure over sensitive areas such as face, eyes, arteries, veins, or nerves.

Practitioners using tissue flossing should consider indications, precautions, contraindications, intervention descriptions, patient assessment, monitoring, and band hygiene and care.

For detailed info, see https://doi.org/10.26603/001c.94598