Walking as a Rehabilitation Exercise for Clients with Chronic Lower Back Pain

Walking is commonly recommended to relieve pain and improve function in patients with chronic lower back pain. A systematic review by Italian researchers addressed the effectiveness of walking interventions by looking into published randomized controlled trials which compared walking to other physical activity exercises to reduce pain, disability, and fear-avoidance, as well as increase quality of life for patients experiencing chronic low back pain.

The authors analyzed data from five randomized controlled trials meeting the determined inclusion criteria. The analysis found that the effectiveness of walking at short-, mid-, and long-term follow-ups appeared statistically similar to other physical exercise rehabilitation protocols.

The authors concluded that pain, disability, quality of life, and fear-avoidance similarly improve with walking when compared to other physical exercise rehabilitation protocols for patients with chronic low back pain. Therefore, walking may be considered to be an alternative to these other physical activity exercises. Given that walking is likely both less expensive and logistically easier for the patient to do than many other forms of exercise, walking should be considered as a viable rehabilitation choice for patients with chronic low back pain. Nevertheless the authors added that further studies with larger samples, different walking dosages, and different walking types should be conducted.

Mechanisms of Rehabilitation

The question should be asked: Why might walking be helpful for patients with low back pain? Although many mechanisms might be proposed, some likely scenarios are that walking strengthens, stretches, and mobilizes the myofascial tissues/joints of the lumbosacral-hip joint region.

- Strengthening

By reaching forward and backward with the lower extremities, the muscles of the hip joint engage by concentrically and eccentrically contracting, coupling with isometric contraction engagement of lumbosacral musculature to stabilize the pelvis and lumbar spine, thus leading to strengthening of the myofascial lumbosacral-hip joint complex.

- Stretching

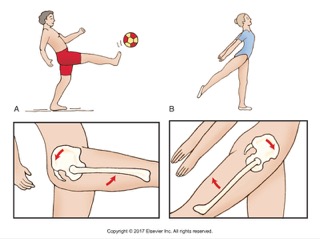

Further, as joints move in one direction, myofascial tissues on the “other side” of the joints lengthen and stretch, allowing for greater flexibility / increased joint range of motion. For example, when the thigh on one side reaches forward to flex at the hip joint, the extensors (gluteals and hamstrings) on that side lengthen and stretch. Simultaneously, when the other thigh reaches back behind the body into extension at the hip joint, the hip flexors on that side in front lengthen and stretch.

- Joint Mobilization

The hip joint, sacroiliac joints, and lumbar spinal joints also mobilize with walking. As one thigh reaches forward into flexion at the hip joint, by femoropelvic rhythm, the pelvic bone on that side, moves into posterior tilt; this occurs as the contralateral thigh reaches back into extension at its hip joint and its corresponding pelvic bone moves into anterior tilt. If one pelvic bone posteriorly tilts while the other pelvic bone anteriorly tilts, motion must be introduced into the sacroiliac joints and pubic symphysis joint, thereby mobilizing them. Further, as the pelvis moves through its posterior/anterior tilt actions, the lumbar spine moves upon the sacrum, resulting in mobilization of the lumbar spinal joints (lumbopelvic rhythm): posterior tilt of the pelvis results in flexion (lordotic motion) of the lumbar spine; anterior tilt of the sacrum results in extension (kyphotic motion) of the lumbar spine. The aforementioned movements only consider the sagittal plane motions of the region. Similar lumbosacral-hip joint couplings of motion occur in the frontal and transverse planes.

And…

- Being a weight-bearing exercise, walking will also help to strengthen bone tissue in all bones involved in weight-bearing joints.

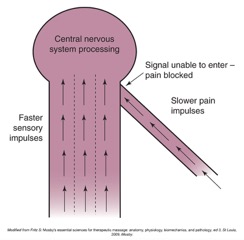

- By the gate theory, the movement involved in walking tends to dampen the experience of pain, thereby directly alleviating pain in the short run, as well as allowing greater physical activity and movement that tends to further the rehabilitation process in the medium and long run.

- Movement results in greater arterial, venous, lymphatic, and synovial fluid movement throughout the body, feeding nutrients to tissues, draining waste products of metabolism, and feeding articular joint cartilage.

- Movement allows for greater proprioceptive input into the nervous system that tends to improve the grace and fluidity of motion, thereby improving proper neural control of posture and movement patterns.

- Any exercise, including walking, also tends to have psychological, psychosocial, and emotional benefits as well.

Image used with permission Joseph E. Muscolino. Kinesiology: The Skeletal System and Muscle Function, 3ed (Elsevier, 2017).

For all these reasons, as well as likely many more, walking is an excellent inexpensive, low-tech, and easy to perform (little or no learning curve is required) rehabilitation exercise that should be recommended as a viable rehabilitation approach for all patients with chronic low back pain.

Precautions/Contraindications

Of course, all rehabilitation protocols, including walking, involve physical forces into the body that may do harm and injure the patient if introduced too forcefully or too quickly without the proper graded introduction to the exercise. Further, the patient might have certain conditions that would contraindicate walking, for example, arthritic/painful weight bearing joints. But short of a few precautions/contraindications, walking is an excellent rehabilitation choice for most all patients with subacute and chronic low back pain.

This article is written in collaboration with Dr Joe Muscolino at www.learnmuscles.com